Microbiota Communities of Healthy and Bacterial Pustule Diseased Soybean

Article information

Abstract

Soybean is an important source of protein and for a wide range of agricultural, food, and industrial applications. Soybean is being affected by Xanthomonas citri pv. glycines, a causal pathogen of bacterial pustule disease, result in a reduction in yield and quality. Diverse microbial communities of plants are involved in various plant stresses is known. Therefore, we designed to investigate the microbial community differentiation depending on the infection of X. citri pv. glycines. The microbial community’s abundance, diversity, and similarity showed a difference between infected and non-infected soybean. Microbiota community analysis, excluding X. citri pv. glycines, revealed that Pseudomonas spp. would increase the population of the infected soybean. Results of DESeq analyses suggested that energy metabolism, secondary metabolite, and TCA cycle metabolism were actively diverse in the non-infected soybeans. Additionally, Streptomyces bacillaris S8, an endophyte microbiota member, was nominated as a key microbe in the healthy soybeans. Genome analysis of S. bacillaris S8 presented that salinomycin may be the critical antibacterial metabolite. Our findings on the composition of soybean microbiota communities and the key strain information will contribute to developing biological control strategies against X. citri pv. glycines.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the world will be demanding more food than the amount of productivity of crops in the near future (Jägermeyr et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019b). By 2050, the world’s population will reach 9.7 billion, and the food supply will face difficulties due to reduced crop productivity (Chen et al., 2016; Jägermeyr et al., 2020; Lau et al., 2017; Rodriguez and Durán, 2020). These issues increased the request for a second green revolution in agriculture. They led to the emergence of the concept of the plant microbiome and promoted research activity in related fields (Reverchon and Méndez-Bravo, 2021). The plant microbiome has all surrounded factors to protect well-grown plants, such as microbe factors mutually interacting in a beneficial direction (Dini-Andreote and Raaijmakers, 2018; Xiong et al., 2021). All the plant-associated microorganisms are expanded from soil to flower. Also, their living spaces are categorized as below-ground: rhizosphere, root episphere, root endosphere, and above-ground: episphere, endosphere, anthosphere, and seed (Bintarti et al., 2022; Hannula et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019a, 2019b; Lu et al., 2018; Simonin et al., 2022).

The soybean is the most important crop for providing protein, and the crop is known for being essential for a wide range of agricultural, food, and industrial applications. Also, it is the world’s most cultivated annual herbaceous legume (Jeong et al., 2019). However, the primary crop has been faced with the loss of productivity by climate change and increased damage caused by various disease occurrences. Among diseases in soybean, root rot disease caused by Fusarium solani, is the most devastating disease. Interestingly, nodulation root by Rhizobia showed less damage by the fungal pathogen (Ikeda et al., 2008). Research on microbiota communities has been conducted with soybeans, and the diversity of microbiota is known to contribute to ensuring healthy and high-quality soybean productivity (de Almeida Lopes et al., 2016). Rhizospheric microbes demonstrate crucial roles in shaping rhizobia-host interaction. For example, Bacillus groups regulate the growth of sinorhizobia and bradyrhizobia and promote nodulation under saline-alkali conditions (Han et al., 2020). Endophytic bacteria Acinetobacter, Variovrax, Burkholderia, and Pseudomonas species are associated with field-grown soybean (de Almeida Lopes et al., 2016). In general, endophyte microbes have more dependent on the host plant (Mingma et al., 2014). Bacterial endophytes are inhabitants inside the plant tissue, and these provide beneficial mechanism roles that prevent pathogen infection and promote host growth (Orozco-Mosqueda and Santoyo, 2021; Xiong et al., 2021). Also, the symbiotic relationship between endophytes provides various secondary metabolites to the host plant (Dang et al., 2020). Despite consistent evidence of the beneficial microbe interaction with the host, it is remained a challenge to identify host genetics and plant microbiome composition (Deng et al., 2021). The diversity and composition of bacterial endophytes are typically studied with high-throughput sequencing methods to explain the microbial community levels (Bintarti et al., 2022). Endophytic communities provide tolerances toward heavy metals, pollutants, and high salinity stresses (Dong et al., 2018; Han et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021b; Longley et al., 2020; Reverchon and Méndez-Bravo, 2021).

Xanthomonas citri pv. glycines, the bacterial pustule disease pathogen, causes a decrease in soybean production and quality worldwide (Kang et al., 2021). The pathogen is infected through natural openings or wounds in plants. To understand and develop control methods for the disease, we need to investigate a piece of microbial ecological information in microbial interaction. However, soybean-associated microbial communities have been rarely studied. Therefore, we investigated the microbiota communities’ structure between infected and non-infected soybean and changes in the abundance of the keystone taxa. Additionally, we also analyzed the genome of a key strain, which contributes to suppressing the bacterial pustule disease pathogen.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth condition

To sterilize, 3 g of soybean seeds (Glycine max cv. Daewon) were transferred into a 50-ml tube, then added 70% ethanol for 30 s. After shaking, the supernatant ethanol was discarded, added 1% NaOCl and vortexed for 30 s. After these steps, the seeds were washed with ddH2O for 2 min, and the washing was repeated three times then, the seeds were placed on a sterilized cotton paper in a petri dish. The plates were incubated for 3 days at 28°C in dark conditions. The germinated seeds were replaced in a plastic squire pot (18 cm × 18 cm). Each pot has more than 20 cm of distance to prevent cross-contamination. The plants were grown in a glass greenhouse, in which conditions were light for 14 h, 28 ± 3°C and dark for 10 h, 15 ± 3°C for 28 days, respectively.

Bacterial inoculation and disease indexing

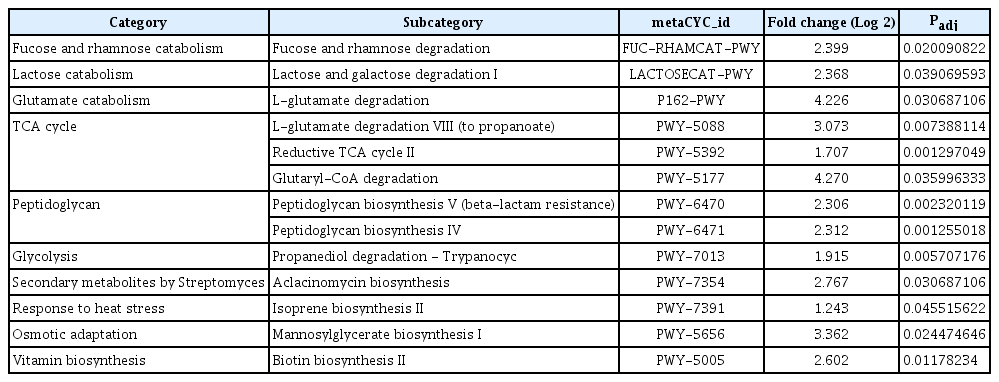

X. citri pv. glycines was streaked on PDK agar (peptone [Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA] 10 g, potato dextrose [Difco] 10 g per liter), and a single colony was inoculated in 10 ml PDK broth and incubated for 3 days at 28°C. The cultured cells were added to 100 ml of PDK broth for 3 days at 28°C. Whereas infected and non-infected treatments were separated by the small greenhouse (length: 5 m), and the pathogen stock (106 cfu/ml) was sprayed on the soybean leaves. Ten days after the inoculation, the pathogen occurred symptoms on the leaves and 5 levels of index evaluated the disease severity; 0, no symptom; 1, less than 10–15 small yellow or brown spots; 2, more than 0.5 cm browning area; 3, darkening and browning area more than 30%; 4, darkening and browning area more than 50%; 5, death (Kang et al., 2021). Non-infected and infected plants were separated into two small greenhouses (3 m × 1.5 m) and the disease index (n = 28) was measured with an independent student’s t-test (P = 0.05).

Xanthomonas citri pv. glycines was re-isolated from the infected soybean leaves, which appeared in disease index value 4. The leaves were cut into 5 mm × 5 mm, sterilized with 70% ethanol for 30 s, 1% NaOCl for 30 s, and washed twice with distilled water. The leaves were inoculated on 1/5 TSA medium (tryptic soya broth 30 g, agar 20 g per liter) at 28°C for 3 days. Colonies growing near the leaves were streaked to another TSA medium for pure culture and extraction of genomic DNA of the pathogen. Genomic DNA was prepared by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Wilson, 2001). For sequencing of the pathogen, the upstream region of the hypothetical protein gene was amplified using XGF (5′-TGTGCGGCCAGTAGATAGTGAGC-3′), XGR (5′-CCGAGGGCCAGCAAAGAAG-3′) primer pairs (Park et al., 2007). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction was carried out with a total of 20 μl of a mixture (1 μl of genomic DNA, 1 μl of each primer [10 pmol], 2 μl of 10× Reaction buffer, 1 μl of dNTPs [10 mM], 0.5 μl of Taq DNA polymerase [500 U; Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea]). The cycling condition was followed: 94°C for 10 min (1 cycle), 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min (25 cycles), 72 °C for 10 min by a T100 thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The PCR products were purified using Expin Gel SV kit (Bioneer), and sequencing was carried out by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea). The sequencing was aligned with the nucleotide BLAST search program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) in NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information). The phylogenetic tree was analyzed using GenBank BLAST with the maximum likelihood algorithm in the MEGA 10 program.

DNA extraction, metagenome, and analysis of microbial community

After 27 days of X. citri pv. glycines inoculation, the non-infected and the infected soybeans rhizosphere, root endosphere, and stem endosphere samples were harvested. The root or stem tissues contained a 50-ml conical tube was filled with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer (10× PBS: 80 g of NaCl, 2 g of KCl, 1.44 g of Na2HPO4, 2.4 g of KH2PO4, adjusted to a pH of 7.4 and a final volume of 1 liter) and was sonicated at 35 kHz for 15 min (Kim et al., 2019a). The sonicated samples were sterilized in 70% ethanol for 30 s, 1% NaOCl for 30 s, washed with ddH2O several times, and then air-dried under a sterilized hood for 30 min. For DNA extraction, 0.5 g of tissue was used. The extraction protocol of FastDNA SPIN Kit (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) followed the manufacturers’ instructions.

For amplification of the V4 region in 16S rRNA, DNA was diluted to 8 ng/μl and amplified using 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′), 805R (5′-GACTACHV GGGTATCTAATCC-3′), which is including overhang adapter sequences, PNA probes (pPNA, mPNA) (Lundberg et al., 2013) to block plant-derived mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA. The PCR reaction was conducted with 2.5 μl of DNA, 1 μl of each primer (10 pmol), 2.5 μl of each PNA probe (7.5 μM), 12.5 μl of KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in the final volume of 22 μl. The PCR condition followed: 95°C for 3 min (1 cycle), 95°C for 30 s, 78°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s (25 cycles). The PCR amplicons were purified using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The amplicons were loaded on 0.8% agarose gels in electrophoresis with 100 V for 20 min (Mupid ExU, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm the amplicon size. Metagenome sequencings were performed with Illumina Miseq by Macrogen.

The raw sequence was analyzed by utilizing the DADA2 software package (Callahan et al., 2016) version 1.8 guidelines (https://benjjneb.github.io/dada2/tutorial_1_8.html) in R version 4.1.3. Libraries were truncated to 265, 215 more than 30 quality scores, merged with forward, reverse reads, and removed chimera sequences. Amplicon sequnce variant (ASV) was assigned to taxonomy by Silva (https://www.arb-silva.de/download/arb-files/) and IDTAXA (Murali et al., 2018), appearing cutoff at 97% similarity. Analyses of richness and evenness were conducted by ggiNEXT (version 2.0.20) and pyloseq (version 3.15). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was shown to visualize using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. Pathway analyses were conducted by DESeq version 3.14 to normalize the fold change value of relative abundance and PiCRUSt2 version 1.1.4 predicted the data to the functional potential of a bacterial community on based their 16s RNA identity (Padj < 0.05), and graph visualization was performed by ggplot2 version 3.3.5. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for statistical analysis (P = 0.05) (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952).

Genome annotation and re-classification of Streptomyces bacillaris S8

Genome sequencing of Streptomyces sp. S8 was performed using the Pacific Biosciences RSII platform (Macrogen) (Jeon et al., 2019). The genome of S8 was re-analyzed and annotated in this study; average nucleotide identity (ANI) with EzBioCloud (Yoon et al., 2017), classification of gene functions by Prokka (v 1.14.6), and the genome were annotated by rapid annotation using subsystem technology 2.0 (RAST 2.0) (Aziz et al., 2008). The classic RAST was set as the default condition, and it functioned by turning on the bacterial domain and automatically fixed error options. A genome map was drawn by ggplot2 (3.3.5) in R (4.1.3 version) based on the Prokka results. The genome information was transformed from gff format to data frame object. GC ratio and GC skew were calculated and plotted by bar graph inner circle in total level and per 10,000 bp. Coding sequence was indicated as a line, and tRNA or mRNA was represented by a black dot in the out circle. Putative secondary metabolites were predicted by antiSMASH bacterial version 6.0 (Blin et al., 2021), in which antimicrobial-related compounds biosynthesis genes were identified in S. bacillaris S8. 16S rRNA gene-based phylogenetic analysis was also performed with a maximum likelihood method. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the MEGA 11 program. Alignment muscles were a gap opening penalty of 15.00 and a gap extension penalty of 6.66. Bootstrap values were obtained after 1,000 re-samplings for each node, and the Jukes-Cantor model was using calculated for the distance.

Antibacterial activity

Three different antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), sallinomycin (≥98%), bafillomycin A (≥90%), and valinomycin (≥99%) were tested for antibacterial effects with a two-layer method (Kim and Kwak, 2021). Solvent conditions were followed: valinomycin in ddH2O, salinomycin, and bafilomycin in chloroform, and each antibiotic was prepared with three different concentrations as 10 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, and 100 μg/ml. The antibiotic solution was inoculated on a filter disk (0.8-mm diam.) and each disk was received 20 μl of the antibiotic and dried for 20 min at room temperature then X. citri pv. glycine was overlaid. The pathogen was cultured in PDK broth (peptone [Difco] 10 g, potato dextrose [Difco] 10 g per 1 liter) for 3 days at 28°C, then 10-ml cultured bacteria were added in 40-ml of pre-cooled 0.2% carrageenan and overlaid onto the antibiotic plates. The plates were dried for 1 h, incubated at 28°C for 3 days and a clean zone around the disk determined the antibacterial inhibition rate. The pathogen growth inhibition assay was repeated 8 times and Kruskal Rank Sum followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (P = 0.05) was used for mean separation.

Results and Discussion

Comparison of microbiota diversity between X. citri pv. glycines infected and non-infected soybean

Microbial communities are significantly contributing to plant health and growth related to the sustainability of agriculture (Dini-Andreote and Raaijmakers., 2018; Xiong et al., 2021). Soybean rhizosphere and endosphere microbiota communities can be changed by various factors such as nodulation, pathogen infection, or genotype of the plant (Han et al., 2020). In this study, we explored the effects of X. citri pv. glycines infection on soybean microbiota community structures. The pathogen-infected soybean appeared with yellow spots and browning areas on the left as disease symptoms and re-isolated the pathogen identified as X. citri pv. glycines (Fig. 1).

Bacterial pustule disease caused by Xanthomonas citri pv. glycines. For disease occurrence X. citri pv. glycines was cultured in 1/5 PDK broth medium for 5 days. The cultured bacteria were adjusted to OD600 0.3 (106 cfu/ml) and sprayed on the leaves of soybeans with a sprayer. After 30 days of inoculation, the severity of bacterial pustule disease was measured using the disease index (n = 28). (A) The disease index value of the soybean bacterial pustule, caused by X. citri pv. glycines. (C) The disease indexes showed a statistical difference according to the treatment groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (B, D, E) Re-isolation and identification of X. citri pv. glycines. Soybean leaves were sterilized and inoculated on 1/5 TSA medium of 28°C for 3 days. (F) Phylogenetic tree of the region of the hypothetical protein (400 bp) in X. citri pv. glycines, the tree was generated with the maximum likelihood algorithm of the MEGA 11 program.

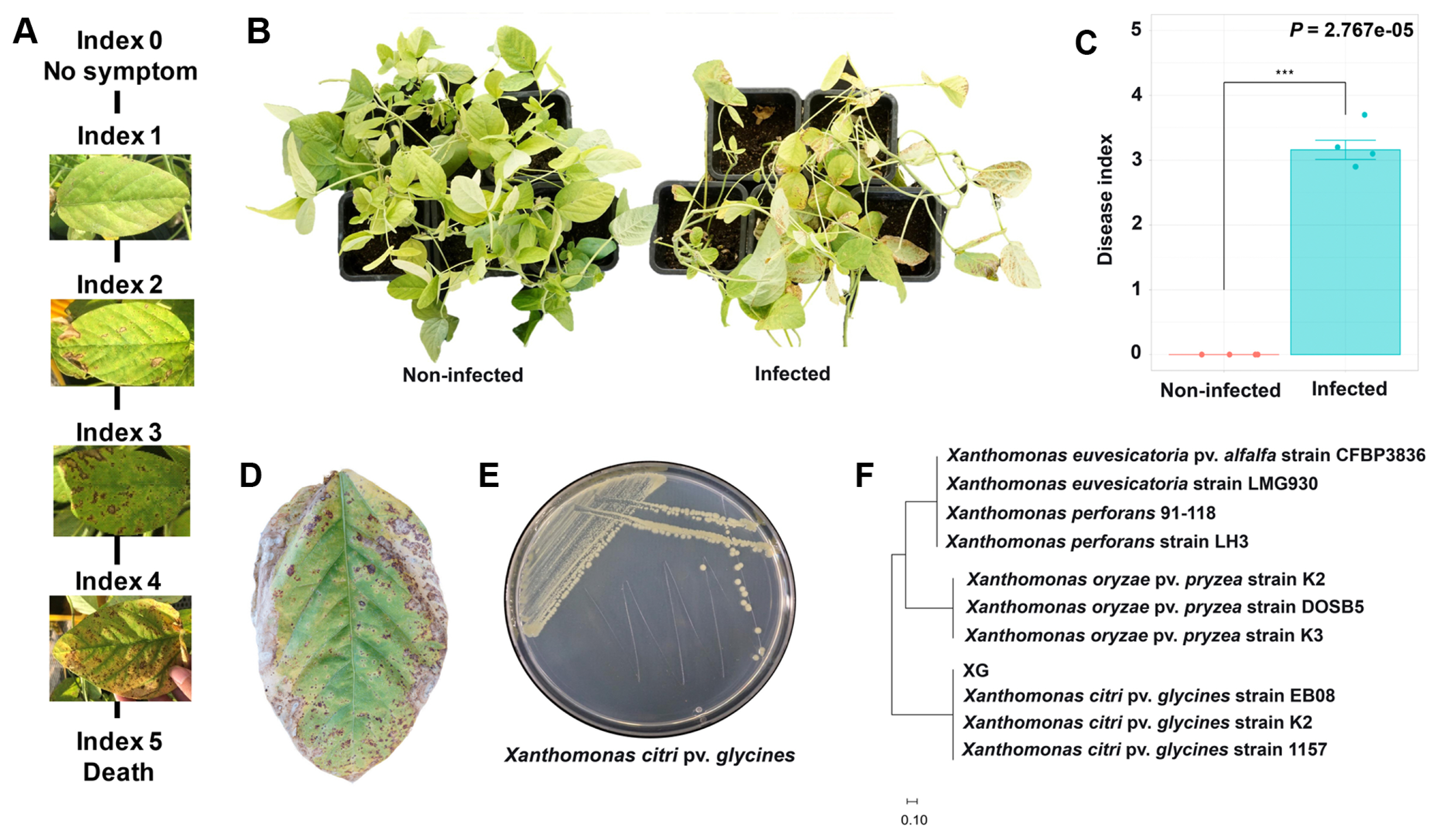

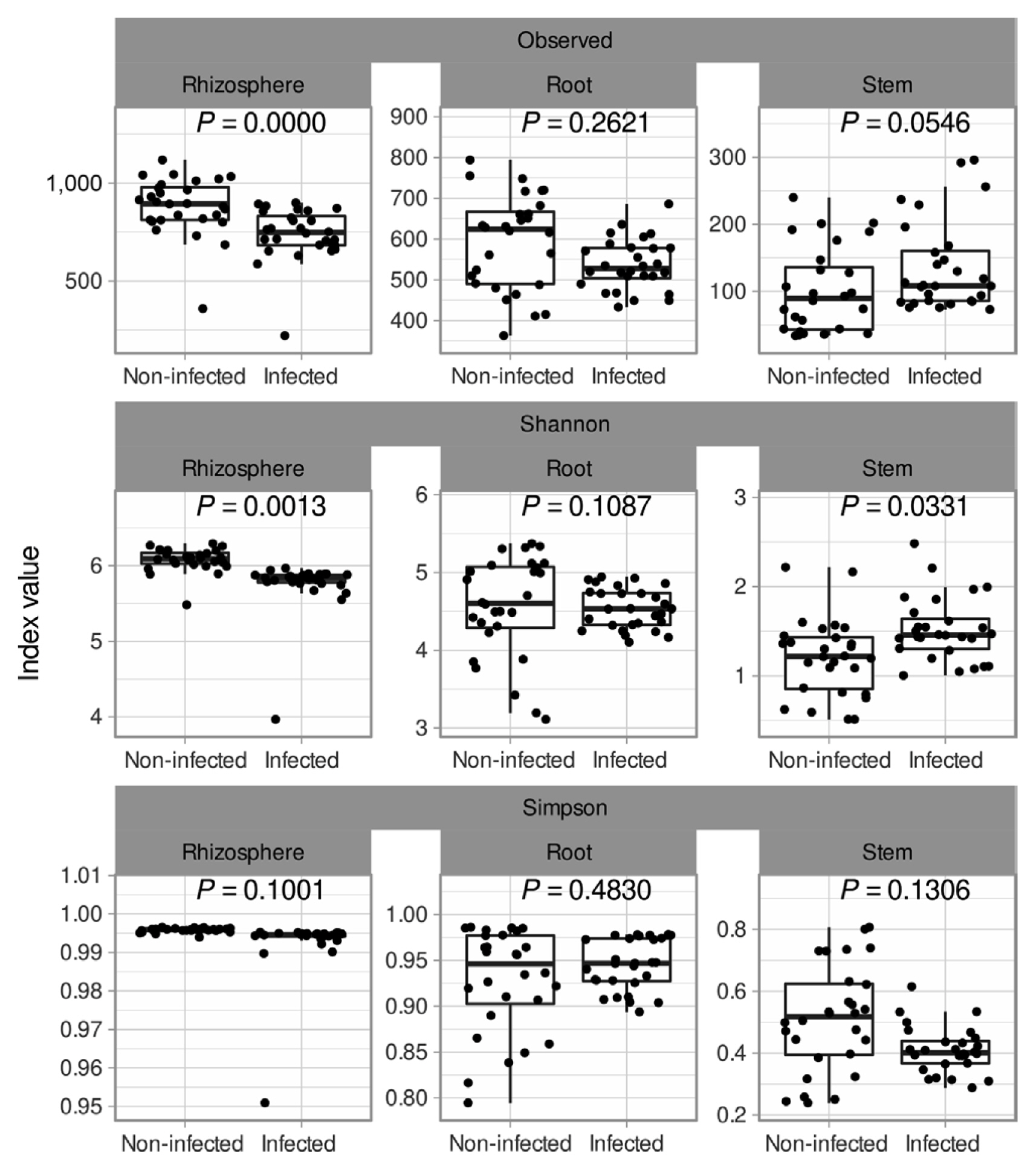

Soybean plants were divided into 3 sections: rhizosphere, root endosphere, and stem endosphere for microbiota investigation. 10,425,683 reads and 6,752 sequences were identified in the rhizosphere, root endosphere, and stem endosphere. All data shows 100 % in Good’s coverage and Chao’s coverage. Total observed ASV was 6,752 and alpha diversity in observed level was a minimum 100 to a maximum 867, Shannon index level was lowest in the stem to 1.3–1.5 and highest was 6 at rhizosphere samples (Fig. 2). In the infection soybean, microbial diversity was decreased by enrichment of Xanthomonadales and Enterobacterales (Fig. 2). But the non-infection soybean was well constructed with microbial communities and presented many bacterial taxa. In the rhizosphere, the alpha diversity of the infected soybeans was lower than the non-infected plants, and the beta diversity was significantly different between the infected and the non-infected soybeans (Padj = 0.001) (Figs. 3 and 4). There was no difference in the alpha diversity in the root endosphere, but the pathogen infection affected the beta diversity (Padj = 0.001) (Figs. 3 and 4). Microbiota at the stem endosphere, alpha diversity, and beta diversity showed a difference in accordance with the disease. At the order level, 20–80% of the total population was Xanthomonadales in the infected stem endosphere. However, root endosphere and rhizosphere microbiota had no dramatic increases in Xanthomonadales (Fig. 2A). The non-infected soybean rhizosphere and root endosphere had similar bacterial communities in top order levels that listed Burkholderialses, Rhizobiales, Chitinophagales, Saccharimonadales, Streptomycetales, Pedosphaerales, Corynebacterialse, Caulobacterales, and Enterobacterales (Fig. 2A). These taxa had a lower abundance at the stem endosphere than the rhizosphere and the root endosphere. Burkholdelaes, Streptomycetes, and Rhizobiales showed more abundance in the stem endosphere of the non-infected soybean. In the infected plant, the rhizosphere and the root endosphere had less changed the microbial community composition. Many types of research presented three microbes crucial role in plant endophytes to against pathogen attack, drought salinity, and growth promotor on their host (Colombo et al., 2019; Hwang et al., 2021; Lopez-Velasco et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019a). But the stem endosphere had dramatically increased the abundance of Xanthomonadaceae and Pseudomonadales. After excluding Xanthomonadales from the communities (Fig. 2B), Enterobacterales was the most abundant taxa in the infected stem endosphere of soybean (Fig. 2B).

Diversity and abundance of bacterial communities in soybean rhizosphere, root endosphere, and stem endosphere. Relative abundance was analyzed at the family level and cutoff in the top 10 (n = 28). (A) Relative abundance between infected and non-infected by X. citri pv. glycines. The ratio of Xanthomonadaceae was low at root and rhizosphere in the untreated group. (B) Relative abundances were recalculated after the removal Xanthomonadaceae.

Species richness and diversity of Xanthomonas citri pv. glycines infected and non-infected soybean. The bacterial taxa were assigned by ID-TAXA, which was machine-learned to confidence in identifying with SILVA 138 SSU. Variables (Observed, Shannon, and Simson) were used alpha diversity. P-value indicated Wilcoxon signed-rank test and removing outlier based on IQR method.

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) to visualize similarities or dissimilarities between Xanthomonas citri pv. glycines infected and non-infected soybean based on Bray-Curtis distance. Statistical analysis was conducted by permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). Shapes of samples appeared organized (rhizosphere, root, stem).

PCoA results presented that microbial community structures were affected by the bacterial pustule pathogen infection (Padj = 0.001). According to the pathogen’s infection, the stem endosphere microbiota was the most significantly affected (Fig. 4). The distance of microbiota communities in root and stem by treatment of X. citri pv. glycines, it can be found that the microbiota of each tissue is different. In the stem of infected and non-infected soybean, microbial communities were not similar, especially Xanthomonadaceae dominated in the infected soybean stem endosphere. It was presumed that the treatment of X. citri pv. glycines on the leaves moved to the stem endosphere. However, except for Xanthomonadaceae from the community in the X. citri pv. glycines infected soybean, the population of Pseudomonadaceae increased in all tissues compared with the non-infected plants. This may result from the genetic similarity between Xanthomonadaceae and Pseudomonadaceae because of the limitations of the pyrosequencing that was analyzed with a limited region of 16S rRNA sequencers (Teeling and Glockner, 2012). Therefore, it may require proceeding with an in-depth phylogenetic analysis along with the previous analysis.

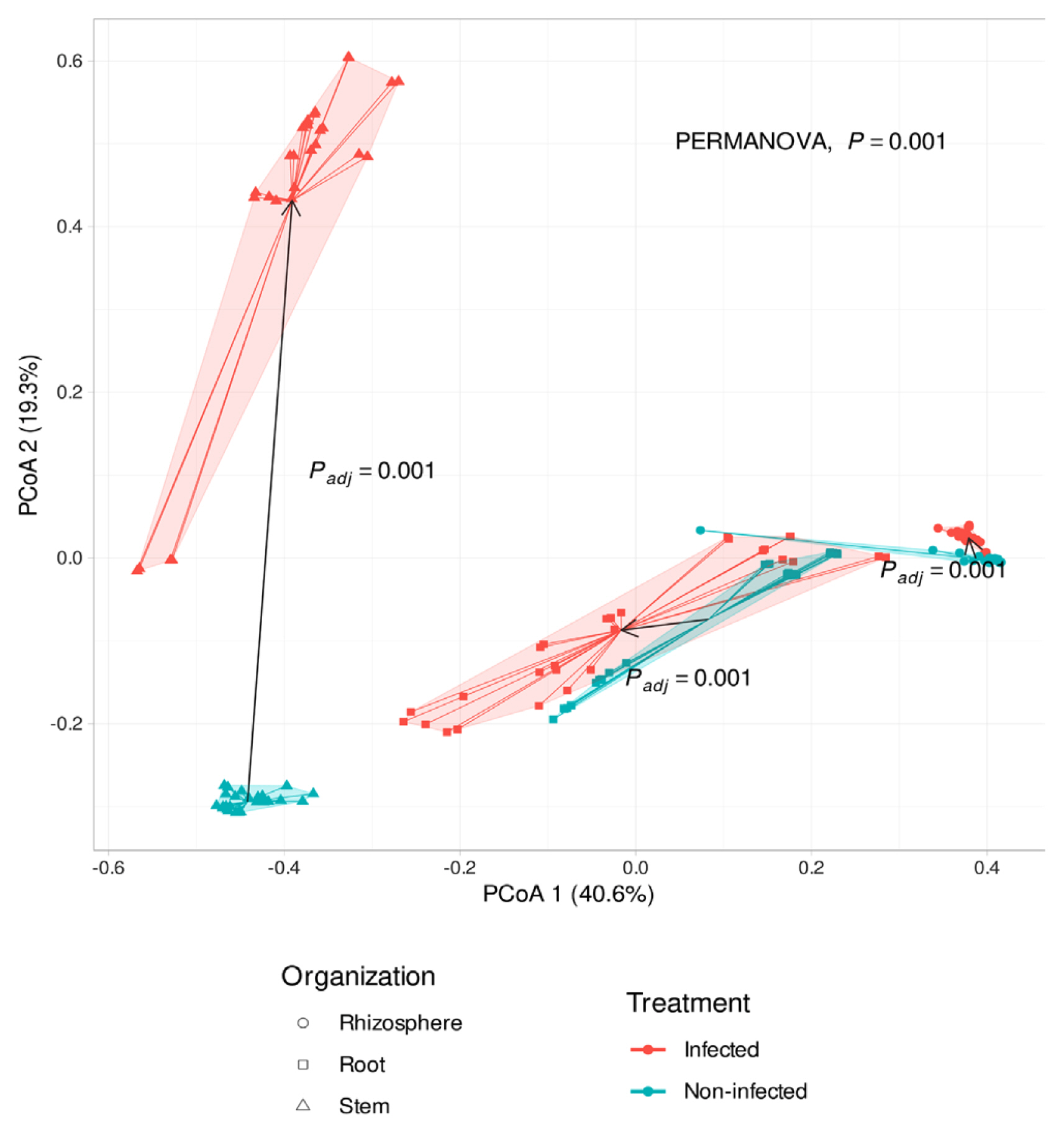

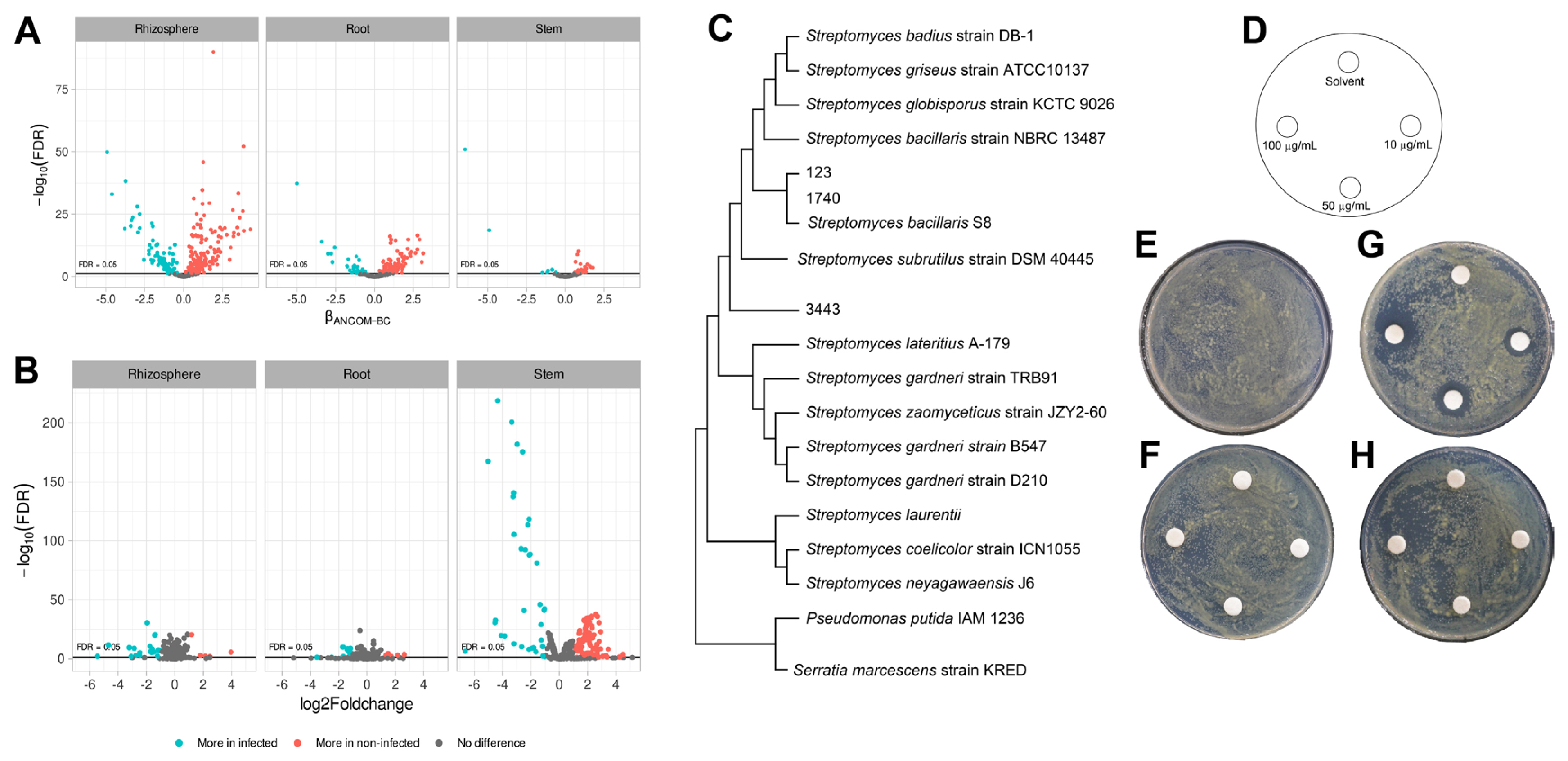

Next, we compared the abundance of taxonomic taxa by Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOMBC). As a result, 159 taxa for rhizosphere, 110 taxa for root endosphere, and 40 taxa for stem endosphere were listed as more abundant in the non-infected soybean. The taxa were Actiomycetaceae, Acidobacteriaceae, Acetobactereaceae, and Burkholderiaceae (Fig. 5A). The most abundant Actiomycetaceae taxa in the non-infected soybean were ASV-123, ASV-1740, and ASV-3443. The ASV-123 and the ASV-1740 showed 99% similarity with S. bacillaris S8 isolated from turfgrass rhizosphere and showed exceptional antibiotic activity (Jeon et al., 2019) (Fig. 5C). And PiCRUSt results suggested that microbiota in the non-infected soybean highly expressed defense mechanisms and carbon metabolism for a bacterial living related metabolic pathway (Fig. 5B). Bacterial carbon and nitrogen sources may be degraded in the stem by lactose and galactose degradation processes, fucose and rhamnose degradation, and sulfolactate degradation composed of the TCA cycle as energy-generating mechanisms (Table 1). And aclacinomycin biosynthesis, osmotic, and heat stress adaptation pathways were also significantly activated (Table 1). Other groups were geranylgeranyl diphosphate biosynthesis, UDP-2,3-diacetamido-2,3-dideoxy-α-D-mannuronate biosynthesis (Table 1), that have known as conducting bacterial immune system (Teheran-Sierra et al., 2021). In the metabolite pathway, the non-infected soybeans microbiota community had many energy metabolite pathways such as lactose, galactose, fucose, rhamnose degradation. Lactose and galactose degradation at the cleavage of glucose and fucose is a six-carbon sugar found in N-linked glycans on the plant cell surface, and the L-fucose can be used complete source of energy (Villalobos et al., 2015). Also, other pathways are rolled to protect the host, TCA cycle in energy mechanisms, osmotic, and heat stress adaptation pathways. Streptomyces produce secondary metabolite, which is aclacinomycin biosynthesis. These pathways were more active in the non-infected soybean microbiota community than in the infected plant. The finding suggested that the microbiota community was well-established in healthy soybeans.

Differences in the abundance of taxa and pathways between the groups. (A) Volcano plot of residuals between infected and non-infected soybean and estimated with taxa family level. (B) Metabolite pathway expression in bacterial community confirmation using PICRUt2 package version 2.3.0. (C) Phylogenetic tree between Streptomyces bacillaris S8 and Streptomyces sq no. 123, 1740, and 3443 at 16S rRNA region with alignment muscles and MEGA 11 program. (D–H) Antibacterial activity of antibiotics: control (E), valinomycon (F), salinomycin (G), Bafilomycin (H). X. citri pv. glycines spread on PDK agar media by OD600 = 0.3 (107 cfu/ml) and added filter disk (0.8 mm). Plates were cultured at 28°C for 3 days.

Genome analysis and antibacterial activity of S. bacillaris S8

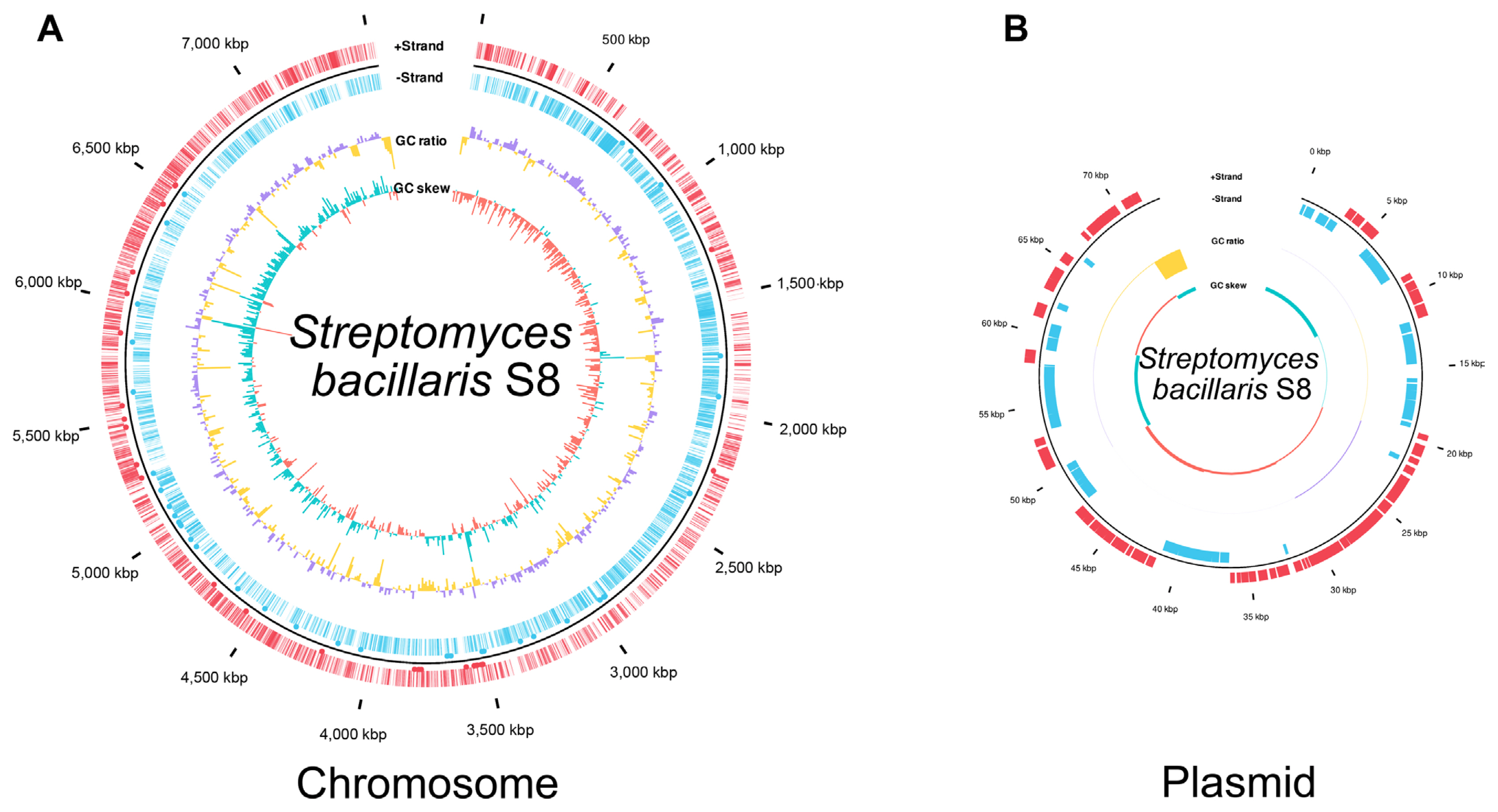

ASV-123, ASV-1740, and ASV-3443 were abundant in healthy soybean stem endosphere, and 16S rRNA phylogenetic results suggested that the ASVs were matched to Streptomyces sp. S8 (Jeon et al., 2019). The strain was re-classified with whole-genome sequences result by EzBioCloud (Yoon et al., 2017), which showed 98% ANI coverage and 95.31% ANI similarity with S. bacillaris and also 16S rRNA, recA, and rplC genes sequences information matched with S. bacillaris at 98% similarity (Table 2). Accordingly, the Streptomyces sp. S8 was re-classified as S. bacillaris S8 (Fig. 6). Biocontrol approaches in plant disease management are highlighted with sustainable agriculture aspect, especially in the genus of Streptomyces, which produces various antibiotic compounds (Kim et al., 2019a, 2021a). Streptomyces sp. S8 was reported as a powerful biocontrol agent against the large patch disease of turfgrass (Jeon et al., 2019). The strain has one chromosome and a single plasmid; the chromosome predicted 9 antibacterial-related metabolite gene clusters by three independent annotation tools (Table 3). Among the 9 putative antibacterial metabolites, salinomycin, valinomycin, and bafilomycin were tested for their antibacterial ability with a plate assay. Only salinomycin showed antibacterial activity against X. citri pv. glycine (Fig. 5D–H). Salinomycin is known to have the effect of disturbing cell membranes (Dewangan et al., 2017). The result suggested that S. bacillaris S8 had dual antibiotic functions as valinomycin for antifungal and salinomycin for antibacterial activities. S. bacillaris S8 may have the advantage of developing as a commercial biological control product.

Streptomyces bacillaris S8 genome reassigned with genome map. (A) S. bacillaris S8 chromosome. (B) Plasmid of S. bacillaris S8. The genome map was drawn by annotation result in Prokka v1.14.6. Marked characteristics are shown from outside to the center; coding sequence (CDS) on forwarding strand (+), CDS on reverse strand (−), GC content, and GC skew. The genome map was drawn using the ggplot2 package of the R (v4.0.3).

Antibacterial gene clusters prediction by antiSMASH, NCBI, and RAST annotation of Streptomyces bacillais S8 genome

We observed and compared microbiota communities in X. citri pv. glycine infection or non-infection soybeans. At the infected plant, microbiota community structures were disrupted, and it caused a reduction of Streptomyces population in the community. The key strain associated with healthy soybean was identified as S. bacillaris S8. Genome analysis and in vitro antibacterial tests, an antibiotic produced by the S8, salinomycin inhibited X. citri pv. glycine. These results suggested that Streptomyces was the key microbe in the microbial community for healthy soybean and presented how microbiota structure studies can reveal the biocontrol agents.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an agenda research program by the Rural Development Administration (PJ015871).