Diagnosis and Integrated Management of Fruit Rot in Cucurbita argyrosperma, Caused by Sclerotium rolfsii

Article information

Abstract

Fruit rot is the principal phytopathological problem of pipiana pumpkin (Cucurbita argyrosperma Huber) in the state of Guerrero. The aims of this research were to 1) identify the causal agent of southern blight on pumpkin fruits by morphological, pathogenic, and molecular analysis (ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2); 2) evaluate in vitro Trichoderma spp. strains and chemical fungicides; and 3) evaluate under rainfed field conditions, the strains that obtained the best results in vitro, combined with fungicides during two crop cycles. Number of commercial and non-commercial fruits at harvest, and seed yield (kg ha−1) were registered. Morphological, pathogenic and molecular characterization identified Sclerotium rolfsii as the causal agent of rot in pipiana pumpkin fruits. Now, in vitro conditions, the highest inhibition of S. rolfsii were obtained by Trichoderma virens strain G-41 (70.72%), T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1 (69%), and the fungicides metalaxyl (100%), pyraclostrobin (100%), quintozene (100%), cyprodinil + fludioxonil (100%), and prochloraz (100%). Thiophanate-methyl only delayed growth (4.17%). In field conditions, during the spring-summer 2015 cycle, T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1 + metalaxyl, and T. asperellum + cyprodinil + fludioxonil, favored the highest number of fruits and seed yield in the crop.

Introduction

The pipiana pumpkin (Cucurbita argyrosperma Huber) is an annual crop cultivated in a traditional agricultural production system, during the rainy season. The crop is cultivated during the months of May and June and is harvested from September to December (Ayvar et al., 2007). The main product obtained from pipana pumpkin cultivation is the mature seed, which has great acceptance for its consumption in different dishes of Mexican cuisine; and is used in the industry as raw material to prepare mole paste. The crop is affected by different phytopathogenic fungi, but those that live in the soil are those that cause severe damages from the beginning of the fruiting stage until harvesting (Diaz et al., 2015). The infection occurs in fruits that are in contact with the soil and the disease development is favored by warm and humid conditions. Infected pumpkin fruits are lost because the pathogens are destructive (Zitter et al., 2004). In this regard, Díaz et al. (2014) mention that the damage of highest economic impact is fruit rot that occurs just before harvest because it drastically reduces seed yield and threatens the successful economic investment of the farmer. To reduce damages, the causal agent must be combated by previous diagnose, through integrated management, where the use of different methods is highly recommended, such as cultural practices, as well as the use of beneficial microorganisms, and the application of chemical products. The use of chemical fungicides is the method that farmers prefer; however, in the state of Guerrero, there is limited information on integrated management of rot in pumpkin fruits. Ayvar et al. (2007) and Díaz et al. (2015) have reported the incidence of oomycetes and deuteromycetes in pipiana pumpkin; they recommend applying specific products such as benomyl and metalaxyl, among others; however, the fungicide validation in the crop is very scarce. In the integrated and sustainable management, control methods must be incorporated in order to reduce the use of chemical molecules, such as applying the genus Trichoderma, a biocontrol agent with high expectations for fungi management in pumpkin, because it has the advantage of being harmless to humans and animals, and does not pollute ecosystems. To achieve success in the integrated management of rot in pipiana pumpkin fruits, it is important to know the history of the cultivated plots taking into account climate information, and the application of biocontrol agents and fungicides in a preventive and never in a curative manner. The aims of the research were: a) to identify, through morphological, molecular and pathogenic techniques, the causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruits, b) to evaluate in vitro the biological effectiveness of commercial and native Trichoderma spp strains, and fungicides and c) to evaluate in the field, under rainfed conditions, the two strains that obtained the best results in vitro combined with fungicides during two consecutive crop cycles.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and purification

In September and October 2014, 20 mature pipiana pumpkin fruits were collected, in a 60,000 m2 commercial plot, established in valle de El Zoquital, Apipilulco, municipality of Cocula, in the northern part of the State of Guerrero, located at the coordinates 18°11 06.30″ North latitude and 99°37′ 36.60″ West longitude, at 620 masl. The typical soil type is loamy-clay, with rainfall and average annual temperature of 1000 mm and 30°C. The W-transect type sampling method was used; where fruits with patches of white fluffy mycelium (in contact with the soil), and with sclerotia were collected. From mature pumpkin fruits, samples with symptoms and signs of rot, five pieces of 0.5 cm2 tissue were cut from the advancing disease area. Samples were disinfected with 1.5% sodium hypochlorite for two minutes, washed three consecutive times with sterile distilled water; 50 tissue samples were placed in Petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated at room temperature (± 28°C) with 12/12 h photoperiod for 5 days.

Morphological identification

The developed fungal colonies were separated and purified by the hyphal tip method in Petri dishes with PDA medium. Temporary preparations in lactophenol were carried out using mycelium samples of the isolated and purified pathogens which were observed in a composite microscope at 40X and 100X lenses, the principal taxonomic characteristics such as color, septation, and branching of the hyphae, as well as the presence of sclerotia was compared to the illustrated keys described by Watanabe (2002); which made it possible to carry out the identification of the fungus.

Pathogenicity test

For the pathogenicity test, five fruit samples were used, washed with running tap water, and the surface was sterilized with 0.2% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 2 min. Then, washed three times with sterile distilled water. Prick inoculation was performed on the fruit epicarp using mature mycelium of the fungus with a sterilized dissecting needle. Inoculated fruits were kept in a moist chamber at 70% relative humidity and incubated for 7 days at 28 ± 2°C. Fruits inoculated with sterile distilled water were used as the control.

Molecular identification

Genomic DNA extraction of the isolates was performed from 7 days old mycelia sample using the DNeasy™ kit (QIAGEN®, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR reactions were carried out using oligonucleotides ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) (White et al., 1990), which amplify the internal transcribed spaces and the 5.8S gene of the ribosomal DNA (ITS region) and generate a product of varying size, between approximately 500 and 600 base pairs (bp) (White et al., 1990). This practice was carried out in the reaction mixture in a final volume of 25 μl, whose final components were 1X reaction buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 nM of each dNTPs, 20 pmol of each primer and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, WI, USA). The thermal program consisted of maintaining a temperature at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94-55-72°C for 30-30-60 s and a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. The PCR-amplified fragments were observed in a UV light transilluminator and sequenced directly on an ABI PRISM® 3700 Genetic Analyzer (Foster City, CA, USA). The consensus sequences were edited and assembled with the CAP option (Contig Assembly Program) (Hall, 2004) of the BioEdit 7.2.5 Software (Tom Hall, Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (Hall, 2004). In the evolutionary analysis, all consensus sequences were aligned with the ClustalW program (Thompson et al., 1994) included in the MEGA 7 software (Kumar et al., 2016). Phylogenetic reconstructions were performed for the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 data based on the maximum parsimony method, using the algorithm Subtree-Pruning-Regrafting, search option (level = 1) with the initial tree by random addition (10 replicates) and the missing spaces were considered as complete deletions. To calculate the confidence values of tree clades, a bootstrap test with 1000 replicates was performed (Felsenstein, 1985). The sequence obtained was deposited in the GenBank database.

Biological control of the causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruits in vitro

Three commercial and three native Trichoderma spp strains; those of the second group were provided by the Laboratory of Phytopathology of the Superior Agricultural College of the state of Guerrero (CSAEGro), which were originally obtained by the plate dilution technique and were reactivated by transferring them in Petri dishes with PDA. Similarly, the commercial isolates were obtained in pure culture, with the same procedure and were reactivated on PDA. The treatments evaluated were: T1: Control, T2: Trichoderma fasciculatum, T3: Trichoderma virens Strain G-41, T4: Trichoderma reesei, T5: Trichoderma asperellum Strain CSAEGro-1, T6: Trichoderma asperellum Strain CSAEGro-2 and T7: Trichoderma sp. Strain Santa Teresa. To evaluate the antibiosis of the Trichoderma strains, the cellophane technique described by Patil et al. (2014) was used; first, cellophane paper was cut in circles of 8.5 cm in diameter, same as the size of the Petri dish; was then sterilized and placed on PDA; with a 0.5 cm diameter cockborer. PDA discs with 3-day old Trichoderma spp colonies were placed in the center of the dish, after incubating for 48 h, the paper with the active Trichoderma spp colonies was removed, so that the secondary metabolites can diffuse in the culture medium, in which the fungistatic effect was immediately evaluated by placing in the center of the petri dish, PDA with mycelium from a 3- day old pathogenic colony and incubating the dishes at room temperature (28 ± 2°C) in the laboratory. A completely randomized design with five replicates was used. The experimental unit consisted of one Petri dish 8.5 and 9.0 cm in diameter, and 1.5 cm in height, with 20 ml of PDA culture medium + Trichoderma spp metabolites. The percent of inhibition was determined by the equation: inhibition % = ((D1−D2)/D1) × (100) where: D1 = diameter of the pathogen colony (control) and D2 = diameter of the pathogen fungal colony growing in Petri dish with PDA medium where Trichoderma spp. had grown (Patil et al., 2014). An analysis of variance and multiple mean comparison test was performed with the data obtained from the variable using Tukey’s honest significant difference method with significance level at 5% (Statistical Analysis System, 2015).

Chemical control of the causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruits in vitro

The experiment was established to study the effect of different fungicides on the development of the identified fungus, using the poisoned culture media technique (Sohbat et al., 2015). The following commercial chemical products were used at the doses recommended by the manufacturer T1: Control, T2: Metalaxyl, T3: Pyraclostrobin, T4: Thiophanate methyl, T5: Quintozene (PCNB), T6: Cyprodinil + fludioxonil and T7: Procloraz, where 20 mL PDA was added to the Petri dishes that contained the doses of fungicide and was allowed to solidify at room temperature (28 ± 2°C). Then a PDA disc (0.5 cm diameter) with fungal mycelium was placed in the center of the Petri dish; they were labeled and incubated in the laboratory. A completely randomized design with five replicates was used. The experimental unit consisted of one Petri dish. To determine the effect of the chemical molecules on the development of the causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruit, the percentage of inhibition was measured in the same manner as described above. Statistical analysis was also similar to that performed in the first in vitro essay. All statistical analysis were performed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 program (Statistical Analysis System, 2015).

Integrated control of the causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruits in field conditions

This phase consisted of evaluating under field conditions, the two most outstanding Trichoderma isolates obtained from the first in vitro essay and the fungicides used in the second in vitro phase.

Experimental site

The experiment was conducted during two crop cycles, in the spring-summer of 2015 and 2016, under rainfed conditions, at the experimental field of the Superior Agricultural College of the state of Guerrero, Cocula, Guerrero (18° 14′ NL, 99° 39′ WL and at 640 masl). The climate is AW0, which corresponds to a warm sub-humid climate with summer rains, average annual temperatures of 26.4°C, and 23.4°C in the coldest month (December). The temperature oscillation from one month to another is from 5 to 7°C. The average annual rainfall is 767 mm. The soil is vertisol with pH 7.1, electrical conductivity 0.23 dS·m−1, organic matter 1.7%, total N 0.1% and phosphorus 14 ppm. The native genotype “Apipilulco”, the most cultivated in the study area was used, reaching maturity at 100–110 days after emergence (d.a.e.).

Treatments and experimental design

A split plot experimental design, with whole plots arranged in completely randomized block design, was used. The whole plots corresponded to two Trichoderma strains, and the sub-plots to fungicides; four replicates were used, the treatments are described in Table 1. The experimental unit consisted of 12 plants, and due to the crop characteristics (indeterminate creeping growth), the entire experimental unit was considered as the useful plot. The treatments were applied twice using an Arimitsu® motorized pump (Model SD-260D, ROGAVAL S.A. of C.V., Mexico State, Mexico), with a 2-point flat-fan KS-K6 nozzle at 80 psi. With a water expenditure of 800 l ha−1. The pH of the water was adjusted to 7 (Agrex® ABC, Agroenzymas S.A. of C.V., Mexico State, Mexico) and the adjuvant (Inex-A®, Cosmocel S.A., Nuevo León, Mexico) was added at a doses of 1 ml.l−1. The Trichoderma strains were applied to the soil at 20 and 35 days after emergence (d.a.e.) and the fungicides, at 60 and 75 d.a.e. The number of commercial fruits harvested in 35 m2 (mature fruits without damage); number of noncommercial fruits also harvested in 35 m2 (mature fruits with some symptoms or level of fungal damage) and seed yield in kg ha−1 were evaluated. Data of each variable were analyzed using individual analysis of variance for each of the cycles and combined through the 2 cycles. Likewise, multiple comparison test using the Tukey method with significance level at 5% was used. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System (Statistical Analysis System, 2015).

Results and Discussion

Morphological identification

Based on cultural and morphological features, the fungal pathogen was identified as Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. [Teleomorph: Athelia rolfsii (Curzi) Tu and Kimbrough]. This fungus is characterized by abundant production of cottony aerial mycelium; rapid aerial mycelium growth (Fig. 1E), septal hyphae, hyaline, branched and thin-walled (Fig. 1A, 1B) with and without clamp connections (fibulas) (Fig. 1C, 1D) forming abundant light brown sclerotia, 1.0–1.5 mm in diameter, globose to subglobose, smooth surface, glossy and compacted (Fig. 1E, 1F) (Watanabe, 2002).

Pathogenicity test

Soft rot symptoms appeared 7 days after inoculating Sclerotium rolfsii in mature pumpkin fruits (Fig. 2 right) in which abundant white cottony aerial mycelium of an aqueous consistency was observed, symptoms and signs were similar to those observed in the field. The control fruits remained healthy (Fig. 2 left). The reisolation of the fungus obtained from the infected tissue of inoculated fruits presented the same morphological characteristics as those that were originally isolated.

Molecular identification

The obtained sequence (570 bp) showed 100% similarity to the ITS region, whose alignment coincided with sequences reported in the Gen Bank for Athelia rolfsii (Curzi) Tu & Kimb [Anamorph: Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc.]. The accession KX757771.1 CSAEGro-CaDIA was deposited in the Genbank of the National Biotechnology Information Center (Fig. 3). The species was identified as A. rolfsii in the phylogenetic reconstruction based on the use of ITS region. The ITS region was able to separate the identified pathogen and the S. rolfsii strain (JX566993), from the rest of the species of the same genus, with a bootstrap reliability of 73%, besides being highly differentiated from the rest of the species (100%) (Fig. 3).

Biological control of Sclerotium rolfsii causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruit in vitro

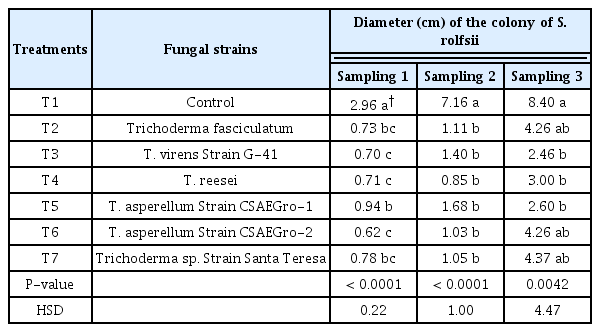

For the three samples of the pathogen growth colonies, the mean values showed highly significant differences (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0042). The lowest growth was observed in treatments with Trichoderma virens strain G-41 (commercial strain) and T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1 (native strain) with 2.46 and 2.60 cm, respectively (Table 2); for these same isolates the highest inhibition percentage of the pathogen was obtained on the last evaluation date (70.72 and 69%) (Fig. 4). The S. rolfsii grew at a rate of 2.8 cm day−1. At the end of the experiment, T. fasciculatum, T. reesei, T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-2 and Trichoderma asperellum Santa Teresa, registered fungistatic activity on the pathogen. There are reports that the secondary metabolites of Trichoderma spp. produces enzymes (glucanases and chitinases), antibiotics (viridina, gliotoxin or peptaiboles) and mycotoxins (Shoresh and Harman, 2008), which are involved in the fungistatic effect Trichoderma produces against fungal pathogens such as S. rolfsii (Hirpara et al., 2017). The results obtained in the present experiment with T. virens are different to those reported by Parmar et al. (2015), who studied, antibiosis of various Trichoderma strains in vitro in the biocontrol of S. rolfsii isolated from peanut. In which, 50% inhibition was obtained with T. virens. In this regard, Hirpara et al. (2017) found that Trichoderma virens presented 76.37% inhibition of S. rolfsii growth in vitro at 144 h; this average effectiveness is similar to 70.72% obtained in the present study, where the maximum inhibition was found using T. virens strain G-41 (PHC RootMate® Plant Health Care, Mexico City, Mexico), but in half the time (72 h). The difference in these results may be explained by the incubation conditions, which may affect the diffusion of secondary metabolites by the biocontrol agent and the pathogen development (Infante et al., 2011). Alvarado-Marchena and Rivera-Méndez (2016) evaluated in vitro the efficiency of Trichoderma asperellum against Sclerotium cepivorum isolated from onion, and found that the pathogen growth inhibition ranged from 47.3 to 61.08%, the maximum inhibition reported by these authors is lower than 69% obtained with T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1, but with the species S. rolfsii. John et al. (2015) evaluated in vitro the antibiosis of different Trichoderma asperellum strains against Sclerotium rolfsii and found that the pathogen growth inhibition ranged from 42.71 to 100.00%, mean values that are within the range and above that obtained by the native T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1. Native strains are an important option to be included in a management plan, as was confirmed in the present study, where the native T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1, was found to be one of the most outstanding biocontrol agents against S. rolfsii in vitro. This agrees with that reported for native T. asperellum strain Csaegro-1, which has been evaluated against Rhizoctonia solani and Phytophthora capsici isolated from pipiana pumpkin, in which the appearance of these pathogens observed in vitro was delayed between 4 and 6 days in inoculated pipiana pumpkin fruits (Díaz et al., 2014, 2015).

Mean values of the diameter (cm) of the colony of Sclerotium rolfsii, in Test I of in vitro antibiosis by the cellophane technique

Chemical control of Sclerotium rolfsii, the causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruit in vitro

In the four sampling dates, highly significant differences (P < 0.0001) were found because all the evaluated fungicides totally suppressed the colony growth of S. rolfsii, with the exception of thiophanate methyl, in which there was an average growth that fluctuated between 0.76 cm in the first evaluation and 8.05 cm at the end of the experiment (Table 3). For the experimental units of the control treatment, the pathogen had an average growth rate of 2.1 cm day−1. At the end of this experiment, the majority of the fungicides inhibited S. rolfsii at 100%, in comparison with the fungistatic activity presented by thiophanate methyl. Khan and Javaid (2015) evaluated the fungicide metalaxyl in vitro, to control the isolate S. rolfsii obtained from chickpea. They reported that this product inhibited the growth of pathogen by 100%. This result is similar to that obtained with the same fungicide against S. rolfsii isolated from pipiana pumpkin in the present experiment. Other studies have evaluated the sensitivity of S. rolfsii in vitro to some fungicides. For example, Mahato et al. (2014) evaluated several fungicides, where the active ingredient metalaxyl inhibited the growth of the pathogen by 94.04%; this percentage is similar to the value obtained with metalaxyl in the present experiment. These results were possible because metalaxyl belongs to the phenylamides group, which inhibits the synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA), affecting mycelial growth, spore formation and pathogen infection (Fishel and Dewdney, 2012). Liang et al. (2015) evaluated the effect of pyraclostrobin on Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, and reported that close to 100% inhibition was obtained when using salycilhydroxamic acid. Without the latter, the inhibition was significantly reduced. On the other hand, Amule et al. (2014) reported that pyraclostrobin inhibited by 100% the development of S. rolfsii in vitro obtained from chickpea. This result is similar to the 100% obtained with this fungicide in the present study. According to Fishel and Dewdney (2012), pyraclostrobin affects mitochondrial respiration that discontinues energy production causing the death of phytopathogenic fungus. In the present study, thiophanate methyl produced fungistatic effect because it allowed 95.83 and 4.17% mycelial growth and inhibition, respectively. These results differ from those reported by Suryawanshi et al. (2015), who obtained the inhibition of S. rolfsii with thiophanate methyl by 63.81%. However, the fungistatic effect of thiophanate methyl observed in the present study coincides with that reported by Manu et al. (2012), because with this same product they registered 0% inhibition on S. rolfsii in vitro; that is, the fungus grew 100% in the culture medium prepared with the fungicide. In the present study, quintozene inhibited the development of S. rolfsii by 100%. In other similar studies, García et al. (2012) found that with quintozene, there were mycelial growth and inhibition by 17.38 and 82.62% in vitro, but against Rosellinia necatrix who is an inhabitant of the soil. Fishel and Dewdney (2012) mentioned that mode of action of quintozene is not fully known, but they propose that it interferes with the synthesis of lipids and cell membranes, which directly affects the mycelial growth of the fungi. The fungicide SWITCH® 62.5 (Syngenta Australia Pty Ltd., Macquarie Park, Australia) (cyprodinil + fludioxonil) was tested in vitro against the mycelial growth of Sclerotium cepivorum isolated from garlic (Allium sativum L.) by Pérez et al. (2015). They found that this product inhibited mycelial growth of the fungus by 1.0 cm, representing 11.76% growth and 88.24% inhibition; inhibition percentage for S. rolfsii lower than 100% was recorded in the present study. On the other hand, Ayala et al. (2015) studied the effect of the fungicides SWITCH® 62.5 WG (cyprodinil + fludioxonil) and Sportak (prochloraz) in vitro on the growth of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolated from bean plants. They reported 100% inhibition of the two products; this value is similar to those obtained in these same treatments evaluated against Sclerotium rolfsii in this study. Mueller and Bradley (2008) commented that cyprodinil inhibits the synthesis of amino acid, and interferes the penetration and fungal growth both inside and outside the area where the product is applied. On the other hand, fludioxonil neutralizes the transduction pathway of the osmotic signal, which affects spore germination and mycelial growth. The azole group of fungicides including the active ingredient prochloraz, which has an inhibitory effect on the biosynthesis of ergosterol, necessary for the formation of cell membranes, permits the adequate pathogen control.

Integrated control of Sclerotium rolfsii, causal agent of rot in pumpkin fruits in field conditions

Number of commercial fruits

Significant differences were found among treatments (P < 0.0001); the averages fluctuated from 12.25 to 29.75. The control obtained the lowest incidence of mature fruits without damage by the pathogen. The highest average was obtained by the native Trichoderma asperellum strain CSAEGro-1 + metalaxyl (T2) (Table 4). On the other hand, during the spring-summer 2015 cycle, more commercial fruits were harvested (Table 4), because in this year there was little rainfall, which lowered the incidence caused by the pathogen. In the combined analysis used to determine the effect of the strain and fungicide of the crop cycles, the best yield was recorded in the spring-summer 2015 season and was obtained by the native T. asperellum strain CSAEGro-1 and the fungicide Metalaxyl (Table 5). Rather et al. (2012) evaluated the effect of metalaxyl and Trichoderma virens strains, against Fusarium oxysporum, Phytophthora capsici, Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii, pathogens that cause wilt in pepper, under field conditions. They reported that with these two treatments when applied individually register averages of disease incidence of 30 and 51.9%, respectively; but when using metalaxyl + Trichoderma virens the disease incidence was significantly reduced to 27.3%. These results coincide with those obtained in this study with Trichoderma asperellum (CSAEGro-1) + metalaxyl, which produced the lowest disease incidence by Sclerotium rolfsii in pipana pumpkin fruits in the field and, consequently, a higher number of commercial fruits were obtained. These findings demonstrate that by combing the different control methods reduces the pathogens damage, which directly affects the harvest of more commercial fruits per cultivated unit area. Number of noncommercial fruits. This characteristic showed significant differences due to the effect of treatments, crop cycles and fungicides (P < 0.0001), but the strains showed a similar behavior. The highest fruit rot incidence was presented by the control, which fluctuated from 2.37 to 11. The lowest fruit damage was obtained by T. asperellum (CSAEGro-1) + metalaxyl (T2) (Table 4). On the other hand, in the spring-summer 2015 cycle, less fruit damage was obtained during harvesting (Table 5). From combined analysis, the fungicide quintozene used in the spring-summer 2015 cycle obtained the lowest damage observed in fruits; On the other hand, the treatments T. asperellum (CSAEGro-1) and T. virens strains (PHC RootMate®) produced similar behavior regarding the fruit rot incidence (Table 5). Islam et al. (2016) evaluated Trichoderma species in controlling tomato stem rot caused by Sclerotium rolfsii; They found that with T. asperellum the disease incidence was reduced; the effect was more consistent when the biocontrol agent was inoculated in the seed and applied to the soil; in the present study similar results was obtained because T. asperellum (CSAEGro-1) decreased the incidence of rot in pipana pumpkin fruits; although the lowest fruit damage was recorded when combing T. asperellum + metalaxyl. In this regard, Mueller and Bradley (2008) argued that the phenylamide group presents systemic properties, so when they penetrate the plant, they are transported systemically to the fruits and protects them against an infection by S. rolfsii. In the analysis of the fungicide effect, quintozene suppressed the incidence of the pathogen and registered lower fruit damage; the positive effect of quintozene was because it affects the integrity of the cell membrane and cell wall, as well as the mitochondria in the phytopathogenic fungi, which decreases the formation of infectious sclerotia and propagules (Latin, 2011). Likewise, the climate played an important role in reducing damages in the 2015 cycle, since the average registered rainfall was only 145 mm, during the growing cycle (June-October). Seed yield in kg ha−1. This component is of great interest because it determines the productivity and profitability that this crop can generate. Significant difference was obtained only by the effect of treatments, cultivation cycle, and fungicides (P < 0.0001). The multiple mean comparison test showed that the highest yields were 901.64 and 883.89 kg ha−1, which were obtained by the treatments T. asperellum (CSAEGro-1) + metalaxyl and T. asperellum (CSAEGro-1) + cyprodinil + fludioxonil, respectively. The highest yield was obtained in the spring-summer 2015 cycle, because less rainfall occurred in this cycle, compared to the spring-summer 2014 cycle (Table 4). The individual effect of the fungicides allowed us to know that the mixture of cyprodinil + fludioxonil was the most outstanding treatment, obtaining the highest seed yield, 862.71 kg ha−1. Although no significant differences were found between the two evaluated strains, T. asperellum (CSAEGro-1) recorded a slightly higher seed yield than the commercial T. virens strain (PHC RootMate®) (Table 5). These results are consistent with Rather et al. (2012), who mention that the use of metalaxyl + Trichoderma sp. reduces the incidence of wilt in pepper (Capsicum annum L.) and promotes higher yields. Akgul et al. (2011) applied several fungicides in the field to control S. rolfsii in peanut, and found that metalaxyl decreased the incidence of the pathogen and also increased yields; the data reported by these authors coincides with the field results obtained in the present study, because the highest yields were produced by metalaxyl and Trichoderma; Finally, Mouden et al. (2016) recently studied the effect of cyprodinil + fludioxonil in vivo to control Botrytis cinerea and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in strawberry; they reported that cyprodinil + fludioxonil was the most effective because it presented 100% inhibition; the effective control of pathogens by using these chemical fungicides corroborates that these products have great potential and should be incorporated into the integrated management of pests and disease, as obtained in the present investigation. These active ingredients protect pumpkin fruits from infection and help to obtain the highest seed yield in the field. The results obtained by Trichoderma are due to its rapid growth, wide ecological plasticity, mechanisms of direct action (competition, antibiosis and mycoparasitism), which manifest their antagonistic potential against plant pathogens such as S. Rolfsii (Infante et al., 2011); this encourages the incorporation of species such as Trichoderma asperellum in the integrated management of this pest and diseases under field conditions, which permits acceptable commercial yields of pumpkin seed as was identified in the present study.

Combined analysis of the treatments including Trichoderma spp. and fungicides on the production of healthy and damaged fruits and seed yield in the cultivation of pipiana squash (Cucurbita argyrosperma), through the 2015 and 2016 cycles