Induction of Drought Stress Resistance by Multi-Functional PGPR Bacillus licheniformis K11 in Pepper

Article information

Abstract

Drought stress is one of the major yield affecting factor for pepper plant. The effects of PGPRs were analyzed in relation with drought resistance. The PGPRs inoculated pepper plants tolerate the drought stress and survived as compared to non-inoculated pepper plants that died after 15 days of drought stress. Variations in protein and RNA accumulation patterns of inoculated and non-inoculated pepper plants subjected to drought conditions for 10 days were confirmed by two dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) and differential display PCR (DD-PCR), respectively. A total of six differentially expressed stress proteins were identified in the treated pepper plants by 2D-PAGE. Among the stress proteins, specific genes of Cadhn, VA, sHSP and CaPR-10 showed more than a 1.5-fold expressed in amount in B. licheniformis K11-treated drought pepper compared to untreated drought pepper. The changes in proteins and gene expression patterns were attributed to the B. licheniformis K11. Accordingly, auxin and ACC deaminase producing PGPR B. licheniformis K11 could reduce drought stress in drought affected regions without the need for overusing agrochemicals and chemical fertilizer. These results will contribute to the development of a microbial agent for organic farming by PGPR.

Drought stress is a limiting factor both in growth and productivity of crops, particularly in arid and semiarid area of the world. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) elicited so called ‘induced systemic tolerance (IST)’ in plants under different abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity through physical and chemical changes. PGPR colonize the rhizosphere of different plant species and confer beneficial effects, either by stimulating plant growth through the biosynthesis of plant growth promoting hormones, or facilitating the uptake of certain nutrients from the soil, and/or reducing the susceptibility to diseases caused by phytopathogenic organisms (Jang et al., 2009; Kandasamy et al., 2009; Kloepper et al., 2004). Many PGPR have 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase activity, conferred IST to plants. Under stress conditions, including drought, the plant hormone ethylene endogenously regulates plant homeostasis and results in reduced root and shoot growth. However, degradation of the ethylene precursor ACC by bacterial ACC deaminase releases plant stress and rescues normal plant growth. PGPR provide plants with fixed nitrogen and soluble phosphate and can control pests by synthesizing bacterial siderophores, antibiotics and hydrolytic enzymes (Hayat et al., 2010; Ortiz-Castro et al., 2009).

Plants are constantly exposed to abiotic stresses, among which drought is a major limiting factor for growth and crop production because it can elicit various biochemical and physiological reactions (Glick, 2004). Abiotic stress tolerance in PGPR has been studied to provide a biological understanding of the adaptation and survival of rhizobacteria under stress conditions (Arkhipova et al., 2007; Creus et al., 1998). Many genetic studies conducted under drought stress have been widely documented (German et al., 2000; Mayak et al., 2004). Although the gene expression by drought stress were recently characterized using molecular and genetic approaches (Kandasamy et al., 2009; Yuwono et al., 2005), their physiological roles with respect to tolerance induced by PGPR are largely unknown in pepper plants. Accordingly, it is critical to identify stress-inducing genes to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in stress tolerance by pepper plants.

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) is one of the most economically important crops worldwide and is widely cultured for its fruits in East Asia (Park et al., 2003). Two dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) and differential display polymerase chain reaction (DD-PCR) (Liang and Pardee, 1992) method has been widely applied in investigations of stress responses (Choi et al., 2002). The present study was conducted to study the molecular effects induced during the pepper-PGPR interaction under drought stress conditions. Additionally, the efficacy of PGPR Bacillus licheniformis K11 in reducing environmental stress in pepper under drought stress was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strain and growth

The PGPR B. licheniformis K11 was isolated from a local field soil in Gyeongsan, Korea (Jung et al., 2006). The PGPR strain was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 28°C for 24 h. B. licheniformis K11 was centrifuged and pellets were re-suspended in 10 ml of sterile distilled water. The plants were then inoculated with bacterial suspension (7.0 × 108 cfu/ml per pot). B. thuringiensis BK4 was used as reference strain (non ACC deaminase producing PGPR), cultured in LB broth at 28°C for 24 h.

Determination of ACC deaminase activity

Qualitative analysis of ACC deaminase activity was performed as previously described (Penrose and Glick, 2003) by measuring the amount of α-ketobutyrate produced when ACC deaminase cleaved ACC. The amount of α-ketobutyrate was determined by comparing the absorbance of a sample at 540 nm to a standard curve of α-ketobutyrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The enzyme activity was calculated based on the μmol of α-ketobutyrate released mg/protein/h. Protein concentrations were determined according to the method described by Lowry et al. (1951) ACC deaminase activity was assayed in bacterial extracts prepared in the following manner. Bacterial cell pellets, were suspended in 1 ml of 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and transferred to a 1.5-ml tube. The tubes were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was re-suspended in 600 ml 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5. Thirty microlitres of toluene were added to the cell suspension and vortexed. The toluenized cell suspension was immediately assayed for ACC deaminase activity. Two hundred microliters of the toluenized cells were placed in a fresh 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube; 20 ml of 0.5 M ACC were added to the suspension, briefly vortexed, and then incubated at 30°C for 15 min. Following the addition of 1 ml of 0.56 M HCl, the mixture was vortexed and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g at room temperature. One milliliter of the supernatant was vortexed together with 800 ml of 0.56 M HCl. Thereupon, 300 ml of the 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine reagent (0.2% 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine in 2 M HCl) were added to the glass tube, the contents were vortexed and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Following the addition and mixing of 2 ml of 2 N NaOH, the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 540 nm. The absorbance of the assay reagents including the substrate, ACC and the bacterial extract were taken into account. After the indicated incubations, the absorbance at 540 nm of the assay reagents in the presence of ACC was used as a reference for the spectrophotometric readings; it is subtracted from the absorbance of the bacterial extract plus the assay reagents in the presence of ACC.

Plant material and stress treatment

Pepper (C. annuum L., Buchon; Seminis Vegetable Seeds, Seoul, Korea) was used as model plant in the present study. The seeds were surface sterilized with 75% ethanol for 1 min and then treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 30 s. Finally the seeds were washed 7 – 10 times with deionized distilled water. After the surface sterilization the seeds were sown in pots (60 × 60 × 58 mm) containing 50 g of sterilized soil (TKS-2, FloraGard, Oldenburg, Germany) and incubated at 28°C and a relative humidity of 50% under a 12 h dark and light cycle with illumination of 5,000 lux until the five-leaf stage. Pepper plants of same size were then selected and transplanted into pots (90 × 90 × 70 mm, one plant per pot) containing 200 g sterilized soil (Lim and Kim, 2009). After 5 days of transplantation, the plants were subjected to experimental treatments. Bacterial strain, incubated at 28°C for 12 h was centrifuged and pellets were collected. The pellets were re-suspended in 10 ml of sterile distilled water. After transplanting for 5 days, pepper plants were subjected to treatments: (I) water irrigation (II) inoculated with B. licheniformis K11 followed by drought stress (III) drought stress. The watering plants were irrigated daily. B. licheniformis K11 was inoculated with 7.0 × 108 cfu/ml per pot by irrigation. For the drought stress treatments, plants were subjected to progressive drought by withholding water for up to 15 days. At the end of the experimental period, the roots of the whole plants were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until used. For protein and RNA abundance analysis, roots were collected 10 days after treatment. The biomass of the pepper plants was also measured after 10 days of drought stress treatment, and the dry mass was determined by completely drying the plants at 70°C. All experiments were repeated 3 times with 10 plants per replication.

2D-PAGE analysis

2D-PAGE and protein identification were conducted by Genomine Inc., Gyungbuk, Korea according to method described by Kim et al. (2006). Total protein extract was separated using an IPG strip with a non-linear pH gradient of 4 to 10 for the first dimension, followed by SDS-PAGE (26 × 20 cm) for the second dimension. Proteins were detected by alkaline silver staining. Quantification of protein spots was carried out using the PDQuest™ software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the quantity of protein in each spot was normalized against total valid spot intensity. For protein identification, protein spots were excised, digested with trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI), mixed with CHCA in 50% ACN/0.1% TFA, and then subjected to MALDI-TOF analysis (Ettan MALDI-TOF, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The ProFound program (http://129.85.19.192/profound_bin/WebProFound.exe) was used to search the NCBInr database for protein identification.

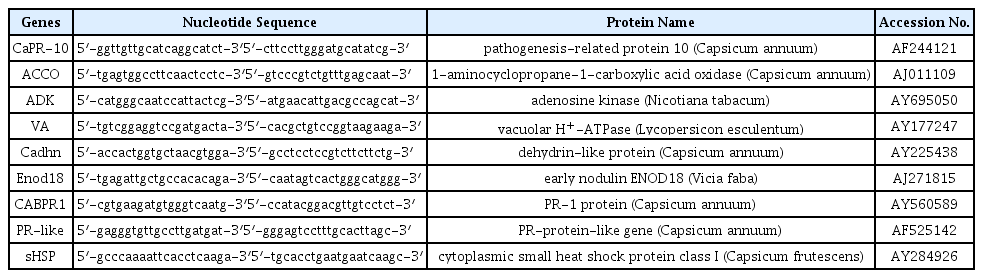

DD-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted through Tri-reagent (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Poly (A+) RNA was purified from total RNA through Oligotex kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cDNA library was constructed by using a ReverseAidTM cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas Inc., Hanover, MD). To search for the differentially expressed genes, 6 genes (CaPR-10, ACCO, ADK, VA, Cadhn, and Enod18) which were more than a 1.5-fold expressed in amount according to 2-DE analysis and 3 genes (CABPR1, PR-like, and sHSP) which mediated adaptation to drought stress by activation or regulation of these proteins were designed (Table 1).

For the differential display analysis, PCR was performed in 50 μl mixtures containing 1 × PCR buffer, 100 ng of DNA and 5 μl of reaction buffer using a template with 1 μl of each 100 pmol primer, 1 μl of 10 mM dNTP and 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (SolGent, Deajeon, Korea). Gradient PCR consisted of 30 cycles of 94°C for 10 min, 94°C for 60 s, 50 – 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s prior to 72°C for 5 min. Amplified PCR products were separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. SYBR Green based real time PCR was performed with the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the reaction was performed as follows: polymerase activation (95°C, 10 min), 50 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 10 s), annealing/extension (58°C, 60 s). The melting curve analysis was performed immediately after the aforementioned amplification process, with the temperature elevated from 65 to 95°C at intervals of 0.2°C. Relative RNA levels were also normalized to the actin (GenBank accession no. AY572427) level.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as the means ± SD from three replicates. Significant difference was verified ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range test at 95% confidence level. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

ACC deaminase activity

B. licheniformis K11 was grow in minimal medium supplemented with ACC, as the sole N source and the ACC deaminase activity of B. licheniformis K11 was assayed (4.16 μM α-ketobutyrate mg/protein). ACC deaminase activity was measured by the amount of α-ketobutyrate (μM α-ketobutyrate mg/protein/h) produced when the ACC deaminase cleaves ACC.

Influence of PGPR strain on the plant growth under drought stress

The growth of pepper plants under drought stress with or without inoculation with B. licheniformis K11 was compared with the water treated plants. Length of root and shoot and dry weight were decreased after drought stress (Fig. 1). However, inoculation increased the root and shoot length and dry weight under drought stress with inoculation. The survival rate of pepper plants was approximately 80% at 15 days after drought stress with inoculation, whereas none of plants survived under drought stress without inoculation.

Induction of drought stress resistance of red-pepper in response to treatment with B. licheniformis K11. (A) plant picture, (B) root length, (C) shoot length, (D) dry weight. B. licheniformis K11 was once treated with 7.0 × 108 cfu/ml per pot. The positive control was watered every 3 days with 50 ml of sterile water. The pictures were taken at the age of 10 days. Values are expressed as the means of three replicates, each containing 10 plants. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range test. Standard errors were determined at P ≤ 0.05.

2D-PAGE analysis

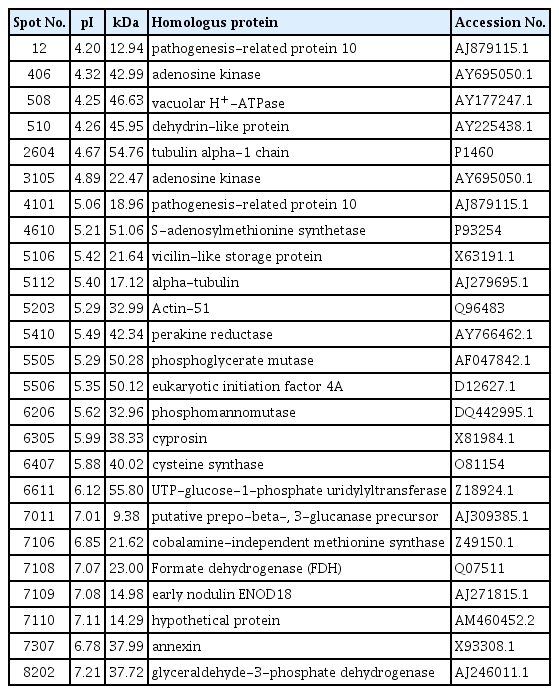

In order to obtain data describing changes in individual protein abundance for pepper plants grown under drought stress conditions, proteins were extracted from roots at 10 days after treatment and 2-DE was conducted. The different proteome gels were compared based on molecular mass and pI of protein spots. Protein spots were reproducibly resolved in gels at similar locations across all replications. Using PDQuest software analysis, 1,206 and 1,081 protein spots were reproducibly detected on 2-DE pattern of drought stress with inoculation and drought stress, respectively (Fig. 2A). In pepper plant roots inoculated with B. licheniformis K11 under drought stress, abundance of 222 protein spots was differentially expressed as compared with drought stress treatment. Among 222 protein spots, most distinct 25 differential spots were sequenced and functionally characterized.

Proteome analysis of the drought stress-related proteins in pepper roots. Drought, drought stress alone for 10 days; Water, watering condition; K11, drought stress with B. licheniformis K11 inoculation (108 cell/pot). In the first dimention, 100 μg of protein was loaded on an 18 cm IPG strip with a linear gradient of pH 4.0 – 10.0 and SDS-PAGE gels were used in the second dimension. The red spots represent the proteins that showed significant differential expression under drought stress with B. licheniformis K11 inoculation as compared with water treatment (A). (B) The differential abundance of proteins was quantified using PDQuest software and plotted as the relative intensity. The white, tilt lines, and square bars indicate water treatments, drought stress without inoculation, and drought stress with inoculation, respectively. Values are the mean ± SE from three replicates. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range test. Standard errors were determined at P ≤ 0.05.

Analysis of differentially expressed proteins

Differentially expressed protein spots in pepper plant with B. licheniformis K11 inoculation under drought stress were identified using PMF. A total of 25 proteins, 6 proteins were abiotic/biotic stress-related or tolerance proteins and these proteins also had more than a 1.5-fold expressed in amount between the two treatments (Fig. 2B). These six proteins showed homology to the following proteins: pathogenesis-related protein 10, adenosine kinase, vacuolar H+-ATPase, dehydrin-like protein, S-adenosylmethionine synthetase, early nodulin (Table 2).

Differential display analysis

DD-PCR was conducted, using nine specific primers to confirm the differentially expressed patterns from the cDNA library of plants under drought stress with/without inoculation and non-stress. Transcript levels of four of these nine genes increased in PGPR-treated roots under drought conditions. However, mRNA of CABPR1, ACCO, PR-like and Endo18 were expressed or unexpressed under both normal and drought conditions (data not shown). These results suggest that PGPR B. licheniformis K11 induced drought stress tolerance of pepper plants via regulation of the stress-related genes investigated. The up-regulated genes were Cadhn, VA, sHSP and CaPR-10 (Fig. 3). The PCR fragments of differentially expressed proteins were excised from the gels and used to determine the nucleotide sequences. Sequence homology was investigated by the NCBI BLAST search. The genes were 99% homologous with Cadhn, VA, sHSP and CaPR-10, respectively (Table 3).

Comparative analysis of stress-related genes in pepper roots under drought stress. Drought, drought stress alone, for 10 days; Water, watering condition; K11, drought stress with B. licheniformis K11 inoculation (108 cell/pot). mRNA differential display analysis of total RNA isolated from pepper roots treated with drought stress. Total RNAs were reverse-transcribed with the primer of stress tolerance-related genes.

Discussion

PGPR have been reported to promote plant growth through either direct or indirect mechanism, or a combination of both. Antibiotics, extracellular hydrolytic enzymes and siderophores are produced by PGPR which, eliminate the pathogenic microbes present in the rizosphere. This type of interaction in plant and microbe is called indirect interaction (Yuwono et al., 2005). However, direct mechanisms include providing plants with phytohormones, fixed nitrogen, soluble phosphate, or iron through bacterial siderophores, or ACC deaminases that can reduce the levels of stress induced ethylene in plants (Glick, 2004).

PGPR strain (B. licheniformis K11) used in the present study produced ACC deaminase and was capable to survive under drought stress condition. The PGPR treated plants that were exposed to drought stress continued to accumulate plant growth. This finding is supported by previous reports demonstrating increased resistance to abiotic stresses including drought stress (Cheng et al., 2007; Kloepper et al., 2007; Sziderics et al., 2007). Furthermore, plant tissues increase ethylene production under abiotic stress, and an increased concentration of ethylene in plants can inhibit plant growth (Bleecker et al., 2000). The ACC deaminase produced by PGPR can reduce a plant ethylene concentration by cleaving the ethylene precursor ACC; consequently, the plants maintain normal growth (O’Donnell et al., 1996; Siddikee et al., 2011). PGPR B. licheniformis K11 might be able to reduce the ethylene concentration of pepper plants by cleaving ACC under drought stress and hence increased plant growth.

PGPR mediated plant stress resistance has been reported in many studies and a numerous genes induced by various stress conditions have recently been identified using molecular approaches (Dardanelli et al., 2008; Egamberdiyeva, 2007; Grichko and Glick, 2001; Saravanakumar and Samiyappan, 2007). However, PGPR-plant interactions with respect to tolerance were largely unknown in pepper plants. Through the 2D-PAGE and DD-PCR approaches, six differentially expressed stress proteins have been confirmed in B. licheniformis K11 treated pepper; PR protein 10, adenosine kinase, vacuolar H+-ATPase, dehydrin-like protein, early nodulin and S-adenosylmethionine synthetase. Gene expression profile during present study indicated that four genes, Cadhn, VA, sHSP and CaPR-10, showed higher levels of expression under drought stress with B. licheniformis K11 inoculation than drought stress without inoculation and non-water-treated pepper. Dehydrins (Group II late embryogenesis abundant proteins) genes are related to drought and cold stresses, and that were found lead to higher accumulation of dehydrin-like protein (dhn) in rye and wheat. Many dehydrins are believed to function via stabilization of large-scale hydrophobic interactions such as membrane structures or hydrophobic patches of proteins (Borovskii et al., 2002). For salinity stress tolerance in plants, the V-ATPase (VA) is of prime importance in energizing sodium sequestration into the central vacuole and it is known to respond to salt stress with increased expression and enzyme activity (Golldack and Dietz, 2001). Pathogenesis-related proteins (PRs) are induced under pathological or other stress-related conditions and play a role in plant defense and development. PR-10 proteins have been shown to be induced by various biotic and abiotic stresses (Yi et al., 2004). Plant small heat shock proteins (sHsps) are produced in response to a wide variety of environmental stressors. sHsps generally function as molecular chaperones that facilitate the native folding of proteins under unstressed and stressed conditions and play an important role during stress by preventing irreversible aggregation of denatured proteins (Sarkar et al., 2009). The response of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (SAM) to stress conditions may stimulate the biosynthesis of lignin. The expression of SAM may be induced upon salt stress because a greater demand of S-adenosylmethionine is imposed by increased cell wall synthesis or modification. Tobacco plants over-expressing S-adenosylmethionine synthetase have been shown to be more tolerant to salt stress than wild type plants under salt stress (Espartero et al., 1994; Kim et al., 1998). Thus, it is assumed that overexpression of Cadhn, VA, sHSP and CaPR-10 may lead to the induction of stress tolerance by pepper plants treated with B. licheniformis K11.

B. licheniformis K11 is multi-functional PGPR strain that simultaneously produces auxins, siderophores and antifungal cellulases, as well as iturin A, an antibiotic compound (Lim et al., 2011). This PGPR strain promotes pepper growth and suppresses phytophthora blight. Multi-functional PGPR B. licheniformis K11 might be useful in the efficient induction of tolerance to both biotic and abiotic stresses that can occur during cultivation of pepper plants.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2010-0008216) and Technology Development Program (107013-03) for Agriculture and Forestry, Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Republic of Korea.