Characterization of the Maize Stalk Rot Pathogens Fusarium subglutinans and F. temperatum and the Effect of Fungicides on Their Mycelial Growth and Colony Formation

Article information

Abstract

Maize is a socioeconomically important crop in many countries. Recently, a high incidence of stalk rot disease has been reported in several maize fields in Gangwon province. In this report, we show that maize stalk rot is associated with the fungal pathogens Fusarium subglutinans and F. temperatum. Since no fungicides are available to control these pathogens on maize plants, we selected six fungicides (tebuconazole, difenoconazole, fluquinconazole, azoxystrobin, prochloraz and kresoxim-methyl) and examined their effectiveness against the two pathogens. The in vitro antifungal effects of the six fungicides on mycelial growth and colony formation were investigated. Based on the inhibition of mycelial growth, the most toxic fungicide was tebuconazole with 50% effective concentrations (EC50) of <0.1 μg/ml and EC90 values of 0.9 μg/ml for both pathogens, while the least toxic fungicide was azoxystrobin with EC50 values of 0.7 and 0.5 μg/ml for F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, respectively, and EC90 values of >3,000 μg/ml for both pathogens. Based on the inhibition of colony formation by the two pathogens, kresoxim-methyl was the most toxic fungicide with complete inhibition of colony formation at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.01 μg/ml for F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, respectively, whereas azoxystrobin was the least toxic fungicide with complete inhibition of colony formation at concentrations >3,000 μg/ml for both pathogens.

Maize (Zea mays L.) is a socioeconomically important crop used in human diets, animal feed and as an industrial resource. Based on the starch composition of the endosperm in the seed, three maize varieties, normal corn (or non-waxy corn), waxy corn and sweet corn, have been widely cultivated in South Korea (Sa et al., 2010). The starch in waxy corn consists of amylopectin while normal corn contains 75% amylopectin and 25% amylose (Nelson and Rines, 1962; Sprague et al., 1943). Sweet corn is a variety of maize with a high sugar content. Waxy corn or sweet corn is mostly used for human consumption in various foods, while normal corn is used for commercial purposes, including chemical products, vegetative oil and biofuel. In South Korea, the largest maize-producing area is Gangwon province; during 2012, maize was produced on approximately 6,539 ha in Gangwon province, corresponding to 38% of the overall maize production area in South Korea (about 17,001 ha; Kang, 2013). The waxy corn cultivars Yeonnong 1, Mibaek 2 and Miheugchal accounted for >80% of the total maize farming area in South Korea (Kang, 2013; Park et al., 2012). At this time, the consumption and popularity of waxy corn are increasing due to the dietary transition from a rice-based traditional diet to a meat-based Western diet (Park et al., 2008). However, the limited number of waxy corn cultivars, increased area of maize cultivation, continued cropping in the same area and global climate change may lead to an increased incidence of certain diseases, causing significant yield losses.

Plant pathogens have evolved to invade plants, overcome defense mechanisms and colonize plant tissues for growth and reproduction. Several ubiquitous fungal pathogens are thought to cause significant damage worldwide during the maize growing season. These include Ustilago maydis causing corn smut, Exserohilum turcicum causing leaf blight (or northern corn leaf blight), Cochliobolus heterostrophus causing seedling and leaf blight (or Southern corn leaf blight) and Fusarium (teleomorph Gibberella) species causing ear rot, stalk rot and seedling blight (Choi et al., 2009; Cotton and Munkvold, 1998; Lim and Hooker, 1971; Pataky, 1992; Skibbe et al., 2010; Valela et al., 2012). In particular, several species of Fusarium, including F. moniliforme, F. graminearum, F. temperatum, F. subglutinans and F. proliferatum, are widely found in plant debris and crop plants worldwide (Marasas et al., 1984). These species of Fusarium are important due to their ability to cause disease in important crops, and to produce a variety of mycotoxins such as moniliformin, fumonisin, deoxynivalenol (also known as vomitoxin), beauvericin, fusaproliferin and fusaric acid (Cotton and Munkvold, 1998; Desjardins et al., 2006). Contaminated grains with high levels of mycotoxins can be fatal and long-term exposure to mycotoxins causes health risks (Fotso et al., 2002; Wang and Xu, 2012).

Fusarium pathogens can infect any part of the maize plant from the beginning to the end of the growing season. Stalk rot is a common and severe symptom on maize causing reduced growth, rotted leaf sheaths and internal stalk tissue and brown streaks in the lower internodes. In mature plants, it causes pink to salmon discoloration of the internal stalk pith tissues (Shaner and Scott, 1998). F moniliforme, F. temperatum and F. subglutinans, belonging to the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex (GFSC), and F. graminearum (G. zeae) are associated with stalk rot disease in maize. Unlike the symptoms of Fusarium stalk rot that usually occur in warm and dry regions, Gibberella stalk rot occurs in cool, moist regions and produces tiny black perithecia (sexual fruiting bodies) on infected maize stalks. Both Fusarium and Gibberella stalk rot results in premature death of maize plants by interfering with the translocation of water and nutrients to leaves and developing ears, causing yield losses.

In South Korea, a high incidence of Fusarium stalk rot has recently been reported in several maize fields in Gangwon province (Shin et al., 2014). Many agricultural chemicals to control insects and weeds are used for maize cultivation in South Korea, but no fungicides are available to manage Fusarium stalk rot in maize plants in South Korea, although targeted disease control is essential when growing crops. Therefore, we investigated several waxy corn cultivation fields in Gangwon province, the largest waxy corn-producing area in South Korea, collected stalk rot-infected maize stalks and isolated the causal agents. Based on molecular and cytological analyses, two Fusarium species, F. temperatum and F. subglutinans, were most frequently isolated from the infected stalks. Based on Koch’s postulates, we confirmed that F. temperatum and F. subglutinans were the causal agents of stalk rot disease on maize plants. Here, we further investigated the in vitro efficacy of six fungicides-tebuconazole, difenoconazole, fluquinconazole, azoxystrobin, prochloraz and kresoxim-methyl-against the two pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and isolation of Fusarium species

Maize tissues with symptoms of stalk rot from maize fields in Gangwon province, South Korea, during 2013 and 2014 were brought to the laboratory in paper bags, air-dried for 24 h and cut into 5-mm pieces. The pieces were placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA; MBcell, Seoul, Korea) separately and grown at 25°C in the light for 2 days. The growing fungal hyphal tips were transferred to PDA and grown for 2 days, and conidia were isolated using the single spore isolation method. Stocks of Fusarium isolates were stored at −75°C in 50% glycerol, among which strains of F. subglutinans KWF-2 and F. temperatum KWF-14 were used in this study.

DNA extraction and molecular identification of Fusarium species

The Fusarium isolates were identified based on a sequence analysis of the translation elongation factor 1 alpha region (EF-1α). For DNA extraction, the isolates were cultured on PDA for 3 days. Afterwards, mycelia were scraped into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes (SPL, Pocheon, Korea). Total DNA was extracted from a mycelium of each isolate using the drilling method described by Chi et al. (2009). The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA was assessed using a BioSpectrometer (Eppendorf, Germany). For molecular identification, the EF-1α gene region of each isolate was amplified with the primers EF1α-F (5′-ATGGGTAAGGAAGACAAGAC-3′) and EF1α-R (5′-GGAAGTACCAGTGATCATGTT-3′) (Amatulli et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2009) in a 50-μl reaction mixture using Pfu DNA polymerase (Elpis, Daejeon, Korea). The amplified products were purified using a Dokdo-Prep PCR Purification Kit (Elpis) and sequenced by Macrogen Inc. (Daejeon, Korea). In the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, BLAST searches of the obtained sequences (600 bp) were performed.

As references, EF-1a gene sequences from five Belgian F. temperatum isolates (MUCL 52445, MUCL 52450, MUCL 52451, MUCL 52454 and MUCL 52462) and three F. subglutinans isolates from the United States, Belgium and South Africa (NRRL 22016, MUCL 52468 and ATCC 38016, respectively) were included in this study (Kriek et al., 1977; Scauflaire et al., 2011; Watanabe et al., 2011). All EF-1a gene sequences were aligned using ClusterW in the MEGA 6 program, and a phylogenetic analysis of EF-1a gene sequences was performed using the neighbor-joining method (1,000 bootstrap replicates) (Saitou and Nei, 1987).

Morphological and cultural characteristics of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum

F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were further identified based on morphological characteristics, as well as a sequence analysis of the EF-1α gene. The isolates were grown on carnation leaf agar (CLA) (20 g of SIGMA agar, 1,000 ml of distilled water and sterile carnation leaf pieces [5 mm]) for 6 days and conidia were collected with 5 ml of sterilized distilled water. Conidiation was measured by counting the number of collected conidia using a hemocytometer. The morphological characteristics of the conidia were analyzed using differential interference contrast microscopy (Axio Imager.A2; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The shape and length of 100 randomly selected conidia were recorded. To determine the colony characteristics, isolates were grown on PDA and the colony diameters and colors were measured using three replicates after incubation for 4 days.

Mycelial growth inhibition of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum

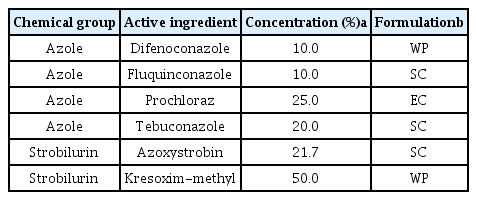

Six fungicides (Table 1) were analyzed to determine their 50% effective concentration (EC50)/EC90 values for the inhibition of mycelial growth and EC100 values for the inhibition of conidial growth. To analyze the inhibition of mycelial growth by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, three replicate PDA plates (90 mm in diameter) containing the fungicides were prepared at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1,000 and 3,000 μg a.i./ml, as described by Matheron and Porchas (2000). The control plates contained only PDA. Mycelial agar plugs (5 mm in diameter) were removed from the edge of the actively growing mycelia of the pathogens and placed at the edge of the prepared PDA plates. Four days after inoculation of the pathogens at 25°C in darkness, linear growth of the mycelia was measured and the inhibition rate was compared to the absence of the fungicide. This experiment was conducted in triplicate and repeated three times. All data were processed with the SigmaStar statistical software package (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The concentration of each fungicide causing a 50% (EC50) or 90% (EC90) reduction in mycelial growth compared to the absence of the fungicide was estimated referring to Matheron and Porchas (2000) and based on the estimated values.

Pathogenicity test of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum on maize

Conidia of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were harvested by scraping the surface of 3-day-old PDA plates flooded with sterile distilled water (SDW) using the bottom of a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube. Mycelial fragments were removed by filtration through two layers of Miracloth. The conidia were pelleted by centrifugation, washed and diluted to approximately 4×106 conidia/ml in SDW. A total of 20 seeds of Mibaek 2 (Park et al., 2007) were planted in pots containing sterilized soil and placed in a greenhouse. A conidial suspension (1 ml) of F. subglutinans or F. temperatum was injected into stalks of the 3-week-old maize plant using sterile needles. Rotted stalks were photographed 5 days after inoculation.

Inhibition of colony formation by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum

Conidia of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were harvested by scraping the surface of 4-day-old PDA plates flooded with SDW using the bottom of a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube. Mycelial fragments were removed by filtration through two layers of Miracloth. The conidia were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 min, washed and diluted to approximately 1×103 conidia/ml in SDW. PDA plates (90 mm in diameter) containing the fungicides were prepared at concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1,000 and 3,000 μg a.i./ml as described by Matheron and Porchas (2000). The diluted conidial suspensions (300 μl) were spread on the prepared PDA plates using a sterile glass spreader. After incubation of the conidia for 3 days at 25°C in darkness, visible colonies were counted. This experiment was conducted in triplicate and repeated three times.

Results

Identification and phylogenic analysis of Fusarium species within the GFSC from rotted maize stalks

In maize cultivation fields in Gangwon province, young plants showed severe stalk rot symptoms, including rotted leaf sheaths; wilting, decayed internal stalk tissues; stunting and leaf death (Fig. 1). From the stalk rot-infected plants, a total of 50 fungal isolates were isolated and purified using single spore isolation. DNA extracted from the collected isolates was used to amplify the EF-1α gene. After BLAST searches against GenBank, the fungal isolates were identified as Fusarium species: 21 isolates of F. subglutinans, 27 of F. temperatum and 2 of F. proliferatum (Table S1). This result suggested that F. subglutinans and F. temperatum are mainly responsible for stalk rot disease on young maize plants. Interestingly, F. subglutinans was isolated in geographically distinct areas, including Hongcheon, Yeongwol, Cheuncheon and Wonju. However, F. temperatum and F. proliferatum were isolated only from Wonju and Yeongwol, respectively.

Symptoms of maize stalk rot caused by Fusarium species (mainly F. subglutinans and F. temperatum) in cultivated fields. (A) Typical symptoms of maize stalk rot in cultivated fields, (B) a rotted maize stem and (C) rotted leaves.

To analyze the genetic relationship among the isolated Fusarium species, the EF-1α sequences from Fusarium species were used to construct a phylogenetic tree, together with the reference sequence of EF-1a. The phylogenetic tree constructed for EF-1α was composed of three main clades (Fig. 2). Three distinct clades were identified among the GFSC isolates analyzed. A total of 27 newly characterized isolates, described herein as F. temperatum, and 4 tester strains of F. temperatum were included in two subgroups in the first clade. A total of 24 F. subglutinans isolates were divided with tester strains of F. subglutinans into two subgroups in the second clade, while 2 F. proliferatum species were included in the third clade. The distinctness of the three clades was supported by bootstrap values of 63–100% in 1,000 replicates. It is worthwhile to note that strains of F. temperatum and F. subglutinans were isolated in the same region and different regions, respectively, and distinctly separated in the two subgroups in each clade. This result is consistent with a previous report showing that F. temperatum can be distinguished from F. subglutinans, F. subglutinans is subdivided into two main phylogenetically distinct groups and F. temperatum shows a high degree of genetic diversity due to intra-species mating compatibility (Scauflaire et al., 2011).

A phylogenetic tree generated using the neighbor-joining method based on a comparison of EF-1α sequences from the Fusarium isolates used in this study. The branch lengths are proportional to the number of amino acid substitutions, which are indicated by a scale bar below the tree. The numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values calculated from 1,000 replicates.

Morphological characteristics of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum

The mycelial growth of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum was 44.3±0.4 and 47.6±0.6 mm in diameter, respectively, on PDA at 25°C after 4 days. The pigmentation of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum was similar, being initially white and orange but becoming pinkish white or yellowish violet (Fig. 3A, F). Measurement of conidiation indicated that F. subglutinans and F. temperatum produced 1×106±75.2 and 7×106±34.4 conidia/ml, respectively. The microconidia of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were oval shaped, 8–20.1 (mean = 12.9) and 5.4–20.9 (mean = 8.6) μm long and 0–1-septate, respectively. Both pathogens produced microconidia in false heads on monophialides and polyphialides (Fig. 3D, E, I and J), which is distinguishable from conidial formation in chains of F. proliferatum and F. verticillioides. F. subglutinans produced mostly 3-septate macroconidia with poorly developed basal cells (Fig. 3B and C), while the macroconidia of F. temperatum were usually 4-septate with distinct foot-shaped basal cells (Fig. 3G and H). The macroconidia of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were 33.2–70.8 (mean = 50.7) and 30.7–57.6 (mean = 46.1) μm in length, respectively.

Morphological characteristics of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum. (A–E) F. subglutinans and (F–J) F. temperatum. (A and F) Mycelial growth on PDA and (B and G) three-septate (F. subglutinans) and four-septate (F. temperatum) macroconidia on CLA, respectively. (C and H) Close-up view of basal cells of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, respectively. (D and I) Microconidia in false heads on CLA and (E and J) polyphialides on CLA. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Pathogenicity test of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum on maize

To investigate the pathogenicity of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum on maize, stalks of 3-week-old maize plants were inoculated by injecting a conidial suspension. The plants infected by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum showed severe disease development (Fig. 4B and C). The symptoms caused by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were indistinguishable from those observed in naturally infected maize plants in fields. The inoculated plants showed typical stalk rot disease symptoms, with wilting, stunting, rotting and death of the leaf sheath. After splitting the rotted stalks, the internal stalk pith tissues and vascular bundles turned yellow and brown. These symptoms were not found on non-inoculated plants used as a control (Fig. 4A). F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were re-identified from the inoculated plants, indicating that these pathogens are the causal agents of stalk rot disease on maize plants.

Pathogenicity tests of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum. Conidial suspensions of F. subglutinans or F. temperatum were injected into the stalks of 3-week-old Mibaek 2 using sterile needles. Five days after inoculation, rotted stalks were photographed. (A) An uninoculated control (B) rotted maize stalk inoculated with F. subglutinans and (C) rotted maize stalk inoculated with F. temperatum.

Effect of fungicides on the inhibition of mycelial growth of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum

Since no fungicides are available to control maize stalk rot caused by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, we assessed the effect of several fungicides on pathogen growth inhibition, including tebuconazole, difenoconazole, fluquinconazole, kresoxim-methyl and azoxystrobin. The four azole fungicides (tebuconazole, difenoconazole, fluquinconazole and prochloraz) inhibited the mycelial growth of F. subglutinans most effectively at a concentration of 10 μg/ml compared to the strobilurin fungicides (kresoxim-methyl and azoxystrobin; Fig. 5). At the same concentration, the most effective fungicides for inhibiting the mycelial growth of F. temperatum were tebuconazole and prochloraz, followed by difenoconazole, fluquinconazole, kresoxim-methyl and azoxystrobin. This result indicated that the inhibitory effect of the fungicides on the mycelial growth of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum differed, and that tebuconazole and prochloraz were the most effective against the growth of the two pathogens. The EC50 values for the six fungicides were determined and are shown in Table 2. The EC50 values of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum for the four azole fungicides were <0.1 μg/ml, but the EC50 values of the two strobilurin fungicides were higher than those of the azole fungicides. The EC90 values of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum for the two strobilurin fungicides were >3,000 μg/ml, while the EC90 values for the azole fungicides were lower than those for the two strobilurin fungicides. Among the azole fungicides, the sensitivities of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum to difenoconazole and fluquinconazole differed significantly; the EC90 values for difenoconazole were 1.0 μg/ml for F. subglutinans and 8.0 μg/ml for F. temperatum, while the EC90 values for fluquinconazole were 0.8 μg/ml for F. subglutinans and 1,200 μg/ml for F. temperatum. This result suggests that F. temperatum was more resistant to the two azole fungicides than F. subglutinans.

Effect of difenoconazole, tebuconazole, fluquinconazole, prochloraz, azoxystrobin and kresoxim-methyl on the inhibition of mycelial growth by F. subglutinans (A) and F. temperatum (B).

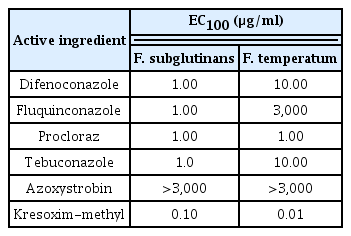

Inhibitory effect of the fungicides on colony formation by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum

Next, we investigated the effect of fungicides on colony formation produced from conidial germination by counting the number of colonies on fungicide-amended PDA plates. Among the six fungicides tested, the strobilurin fungicide, kresoxim-methyl, completely inhibited colony formation by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum at a concentration of 0.1 and 0.01 μg/ml, respectively (Table 3). Unlike kresoxim-methyl, the other strobilurin fungicide, azoxystrobin, was much less effective at inhibiting colony formation by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum. The four azole fungicides inhibited colony formation completely by F. subglutinans at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, showing no difference between the fungicides in the inhibition of colony formation by F. subglutinans. However, the sensitivity of F. temperatum to the four azole fungicides varied; procloraz inhibited colony formation completely by F. temperatum at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, tebuconazole and difenoconazole at 10 μg/ml and fluquinconazole at 3,000 μg/ml. This result indicates that kresoxim-methyl was the most effective inhibitor of conidia-mediated colony formation by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum among the tested fungicides.

Discussion

F. subglutinans, F. temperatum and F. graminearum have been reported as major pathogens causing stalk rot on maize in various countries (Cotton and Munkvold, 1998; Desjardins et al., 2006; Gilbertson et al., 1985; Shaner and Scott, 1998). In our study, F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were frequently isolated from stalk rot-infected maize stalks in corn fields in Gangwon province, suggesting that F. subglutinans and F. temperatum are dominant species. Fusarium graminearum has not been isolated from such stalk rot-infected plants, likely due to unfavorable weather conditions for the development of disease caused by this species. Stalk rot caused by F. subglutinans or F. temperatum usually occurs in warm and dry regions, but that by F. graminearum occurs in cool and moist regions (Gilbertson et al., 1985). However, it is possible that our sample sizes for detecting F. graminearum-causing stalk rot were too small. Although F. subglutinans isolates were detected from different geographic locations in Gwangwon province and F. temperatum isolates were detected only from one location (Wonju in 2003–2004), the fundamental basis for genetic diversity, distribution, migration and population growth of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum in geographic areas remain unclear. In our study, stalk rot disease in maize fields located in Gwangwon province was caused by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum based on Koch’s postulates. The symptoms of maize stalk rot caused by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum were indistinguishable in cultivation fields and pot experiments. However, an analysis of EF-1α sequences together with morphological traits was useful for the identification of the causal pathogens (F. subglutinans and F. temperatum) of maize stalk rot. Determining the cause of symptoms is essential before applying fungicides. Maize stalk rot caused by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum has been a problem in Gwangwon province, but no fungicides are available for the management of the disease.

To investigate the effects of different fungicides on F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, azole and strobilurin fungicides were evaluated in this study. Azole fungicides are sterol demethylation inhibitors (DMIs) that inhibit the C-14 α-demethylation of 24-methylenedihydrolanosterol, a precursor of ergosterol in fungi (Yin et al., 2009). Several field or in vitro studies have shown that DMI fungicides such as tebuconazole, prochloraz and propiconazole can control Fusarium head blight caused by F. graminearum in wheat and Fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum in banana (Ivić et al., 2011; Mesterházy et al., 2012; Nel et al., 2007). For example, Ivić et al. (2011) calculated EC50 values of <0.1 μg/ml for prochloraz and EC50 values ranging from 0.22 to 2.57 μg/ml for tebuconazole in the inhibition of mycelial growth by F. verticillioides, F. graminearum and Fusarium avenaceum. Our study revealed that azole fungicides were more effective at inhibiting the mycelial growth of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum than strobilurin fungicides based on EC50 and EC90 values (Table 2). Consistent with other data mentioned above, prochloraz was the most effective fungicide among the tested fungicides for the inhibition of mycelial growth by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum with EC50 and EC90 values <0.1 μg/ml. However, two azole fungicides, difenoconazole and fluquinconazole, exhibited different levels of inhibitory effects on F. subglutinans and F. temperatum based on their EC90 values; the EC90 value for difenoconazole was 1.0 and 8.0 μg/ml for F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, respectively, while the EC90 concentration for fluquinconazole was 0.8 and 1,200 μg/ml for F. subglutinans and F. temperatum, respectively. Our findings suggest that F. subglutinans is more sensitive to tebuconazole and fluquinconazole than F. temperatum, and that the most effective fungicide is prochloraz, followed by tebuconazole, difenoconazole and fluquinconazole among the tested azole fungicides for the inhibition of mycelial growth by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum. Considering a previous report showing that isolates of F. graminearum, F. avenaceum and F. verticillioides had different sensitivities to several fungicides (Ivić et al., 2011), sensitivity among isolates of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum should be examined in a future study.

Azoxystrobin and kresoxim-methyl are strobilurin fungicides grouped as quinine outside inhibitors (QoIs) that inhibit mitochondrial respiration by binding to cytochrome c oxidoreductase, leading to an energy deficiency due to a lack of ATP (Ma, 2006). Many studies have examined the effects of these two strobilurin fungicides against Fusarium species. Amini and Sidovich (2010) evaluated the EC50 values for benomyl, carbendazim, prochloraz, fludioxonil, bromuconazole and azoxystrbin against the mycelial growth of F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. They suggested that azoxystrobin was the least effective fungicide, with an EC50 value of 1.56 μg/ml, whereas the azole fungicides prochloraz and bromuconazole were the most effective fungicides with values of 0.005 and 0.006 μg/ml, respectively. Menniti et al. (2003) evaluated fungicide effects on Fusarium head blight caused by F. graminearum and F. culmorum in fields near Bologna, Italy. In this study, the azole fungicides prochloraz, tebuconazole, epoxiconazole and bromuconazole controlled the disease, while the strobilurin fungicide kresoxim-methyl was less effective at controlling the disease. In contrast, several studies have shown that strobilurin fungicides are effective against spore germination for many fungal pathogens (Abril et al., 2008; Shin et al., 2008). Shin et al. (2008) reported that kresoxim-methyl and azoxystrobin inhibited the spore germination of F. fujikuroi more effectively than tebuconazole and difenoconazole. Abril et al. (2008) reported that kresoxim-methyl was the most effective fungicide at a 3 μM concentration among other tested fungicides, which prevented the germination of all tested fungal species (Botrysis cinerea, Colletotrichum acutatum, C. fragariae, C. gloeosporioides, F. oxysporum and Phomopsis obscurans), excluding Phomopsis viticola. Fungal conidia are reproductive structures and important vehicles for the colonization of plants, so the inhibition of spore germination with fungicides is essential for chemical control of various plant fungal pathogens. We evaluated the sensitivity of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum to four azole fungicides and two strobilurin fungicides. The counting of germinated conidia on fungicide-amended media is a widely used method for assessing fungicide efficacy (Jaspers, 2001; Matheron and Porchas, 2000). However, in our study, it was difficult to count germinated conidia because the conidia of the pathogens aggregated. As an alternative method, we assessed fungicide efficacy by recording the visible colonies formed on PDA amended with fungicides according to Pappas et al. (2010). Our study revealed that the strobilurin fungicide kresoxim-methyl was the most effective among the tested azole fungicides, whereas another strobilurin fungicide, azoxystrobin, was the least effective fungicide for the inhibition of colony formation by F. subglutinans and F. temperatum (Table 3). These differential effects of the two fungicides are likely due to different binding characteristics to cytochrome c oxidoreductase as kresoxim-methyl and azoxystrobin belong to the oximinoacetate and methoxyacrylate groups, respectively. These results provide basic information on the chemical management of F. subglutinans and F. temperatum.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants (PJ00974602 and PJ009324052014) funded by the Rural Development Administration, and a Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (Plant Molecular Breeding Center, No. PJ0080182014) of RDA, Republic of Korea.